Oliver Klimpel (born in Dresden, East-Germany) is a designer based in London and Berlin. He has been working on various projects for the cultural and commercial sector, i.e. Tate Modern, Museum Folkwang Essen, Goethe-Institute, Taipei Contemporary Art Center. After teaching at Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design and other colleges in the UK, he was appointed Professor at the Academy of Visual Arts Leipzig and has lead the System-Design Class from 2008–2014. He is currently based in Berlin, though one will rarely find him there, as he is continually traveling the globe working on assorted projects. At the moment he’s working on an exhibition about architecture for a museum in Bordeaux, France.

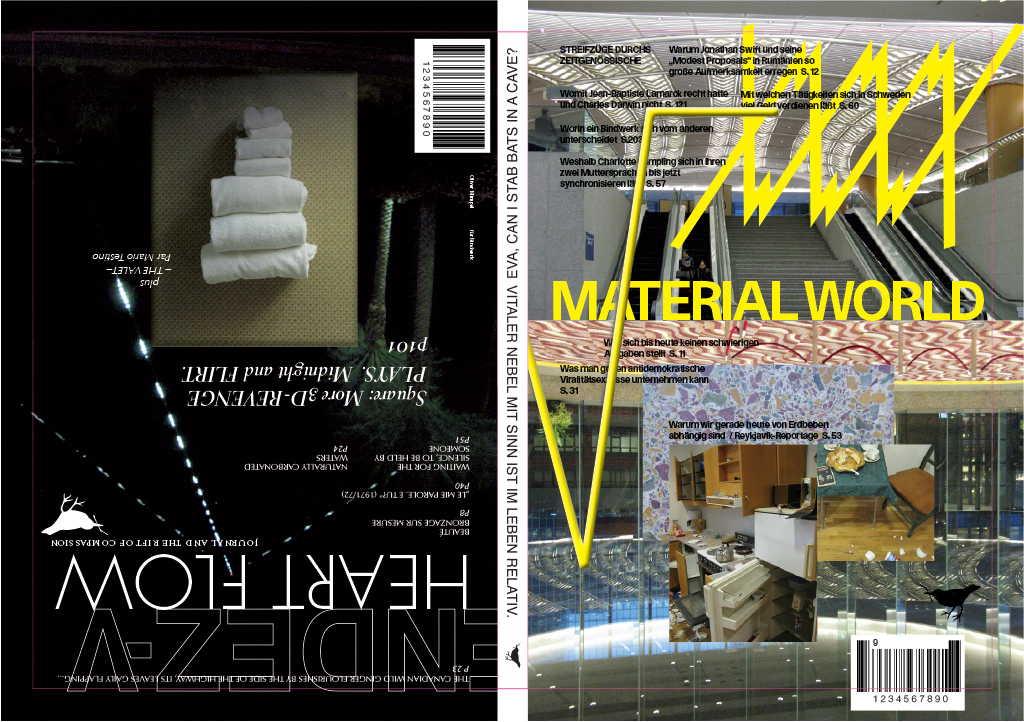

“These are the front and back covers and the spine of a book, which graphics are both fictional, as they are speaking about contents that is not contained inside, as well as factual, as they are designed, printed and bound and hence manifest just as all commercially available magazines are.”

VCFA Co-Chair Ian Lynam became acquainted with Oliver in the summer of 2016 first in Tokyo and then at the 27th Brno Biennial—the longest running design biennial in the world. Ian was curating the Study Room alongside Kiyonori Muroga of IDEA while Oliver was emceeing the event. Each day of live programming started out with a lucid audio/visual presentation given by Oliver that was comprised of poesy, heresy, speculative revisionist history and some outright lies set to a fantastic audio score. Each was a thoroughly entertaining way to start the day, and sealed Ian’s affinity for Oliver immediately, though when they spoke further every day while in the Czech Republic, the two became fast friends.

Oliver is a prolific design teacher, writer, and thinker. He has edited, for instance, “The Visual Event – An Education in Appearances”, a book about design as a non-object-centric but situation-driven practice, and realized and published a collective translation (by 50 contributors) of a JG Ballard science-fiction novel. In the following interview, Ian gets down to brass tacks with Oliver, exploring a panoply of topics design-oriented and not.

“A commissioned work that can be currently seen in an exhibition at the Taipei Fine Art Museum (TFAM) in Taiwan. For another artspace in Taiwan, the TCAC, I developed an ambivalent ensemble of objects that meander between display furniture and artistic artefact, between an object that helps to show art, and a piece of art or sculpture itself. After the exhibition closes these objects will become part of the institutional daily practice of the TCAC. So they’re designed for use – and discourse. This work relates to my interest in “Institutional Critique”.”

Who are your heroes?

I’ve always had a soft spot for polymaths. So, challenging ideas, small or big, or attitudes are often more important than every single piece of work on their own.

A good example would be the architect Hans Hollein, who called himself an “ideas man”. Worked effortlessly between inflatables, shops, wayfinding and museums, advertising and architecture. Or an other architect: Cedric Price, who also taught at the Architecture Association in London. Actually, however different, they are of the same generation of 1960’s trailblazers that combined in their practice the practical with intellectual rigor and playfulness – I find their work still brilliant and relevant. I admire less high degrees of specialization or mastery, but men and women who dare to sincerely and “promiscuously” inquire, ask questions and see where they might lead them. Basically, people who work in diverse media, or forms of expression, and trespass into fields they haven’t been trained in—be it text, images, lumps of clay, or flower arrangements. The marvellous German writer Rainald Goetz – a contemporary – said that if you’re getting really good at something, you should stop and do something else.

Outside of the world of graphics, I have found many peoples’ works inspirational. For very different reasons: filmmakers JL Godard, or Peter Watkins, or the artists Guy de Cointet and William Leavitt. If pressed for some names from the field of graphics, Peter Saville has been providing some spiritual companionship for me, as did Barney Bubbles or the Belgium Benoit Hennebert.

But besides the more well-known or published, I’m very fond of practitioners in visual culture or the arts, who have just stayed true to their interests and their beliefs. They’re probably most suited to the ambigious notion of the hero, or the heroine.

I’m thinking, for instance, Mr Oishi, an Edo-Moji commercial-signwriter from Tokyo, one of only seven (!) remaining practitioners of that craft, who I had the pleasure to get to know and work with last year in May.

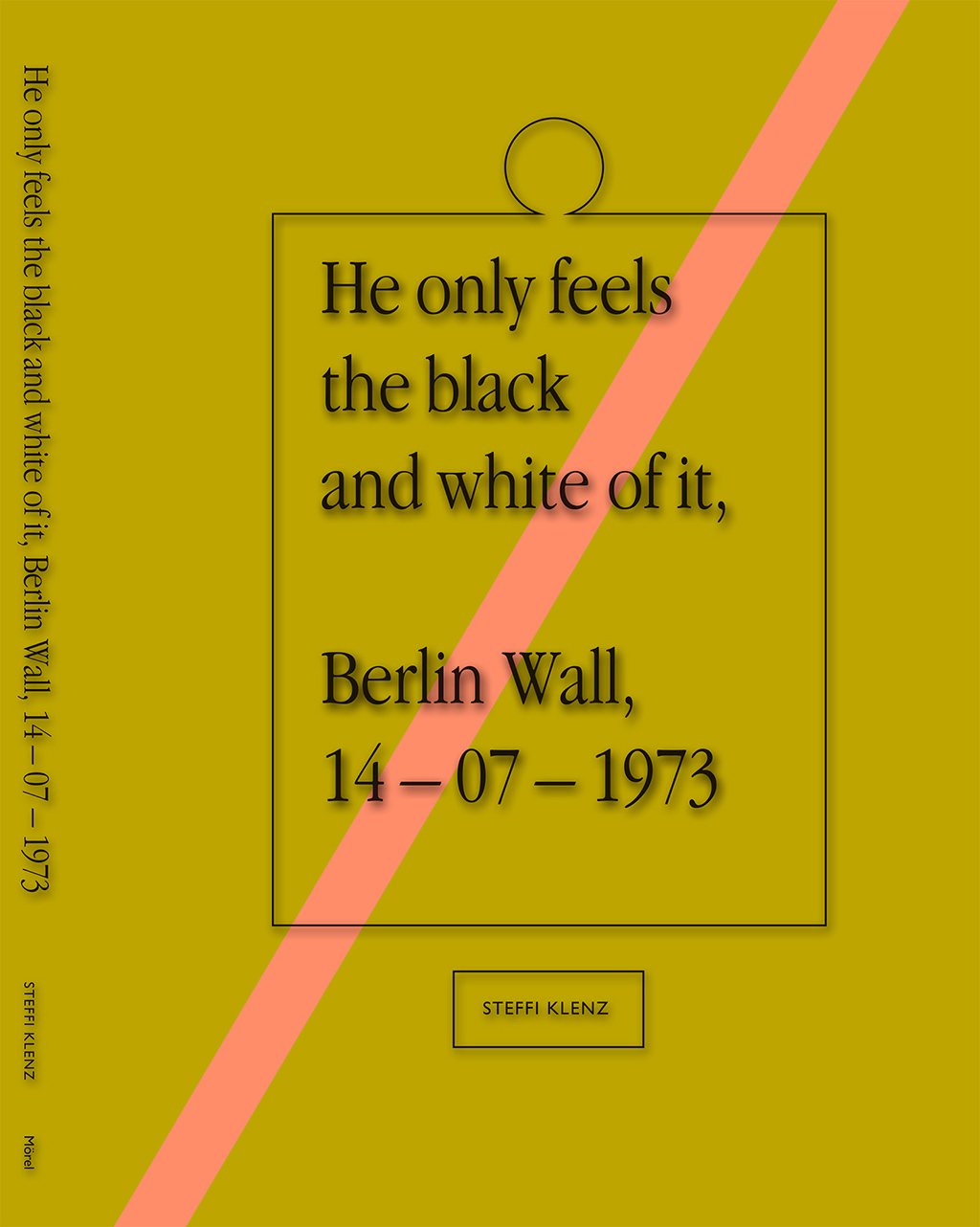

“I design quite a few books and publications, mostly for the cultural sector. This is the cover of the artist book I designed in collaboration with artist Steffi Klenz. It’s a book centered around one Associate Press photograph of the Berlin Wall and daily life and tensions in a family in socialist East-Germany.”

Who are your anti-heroes?

Anti-Heroes are often my heroes, villains might be my anti-heroes. I’m definitely not so interested in hegemonic figures, “leaders of industry”, and designers associated with traditional notions of “quality” or “success”. Often enough, these dominating figures are epigones, emulating and cultivating fringe concepts. I can very much respect that transfer of style or concept, from fringe into the mainstream, but I won’t admire it. Buy me a beer and I’ll dish out some dirt.

What does “heroism” even mean anyway?

The Heroism I’m interested in is a narrative format, a mythology. In other words, one shouldn’t see design heroism as a (by now historical) practice but one of fiction and storytelling. In relations to graphics I find this rather intriguing since such narratives are one way of portraying a practice that seems increasingly harder to portrait. There is just so much you can do with people sitting in front of screens, sketching something down on a piece of paper, or having a discussion… And to produce representations of graphic practice are useful as they will allow us to understand better what it is what we’re actually involved with, how it is perceived and which bits are the ones we see chances for further developing. That’s why I have written fictionalized accounts of real (and some well-known) people in the graphic trade to test out how an identity of graphic practice (and graphic heroism) can be constructed. Like the pieces I had performed at the Brno Graphic Design Biennial that you mentioned in your introduction.

In your 2014 essay “Everybody’s Got to Learn Sometime”, you posit that “social media has killed the underground”—a statement made by many about the death of subculture. Other critics and writers have suggested that we must replace the goals of collective cultural production (formerly the ‘authenticity’ of subcultures) with ‘quality’.

Ultimately, the question for me is how and in which channels non-mainstream production, cultural or otherwise, can interact or impact with mainstream. It is less if these different voices, including transgressive cultures, do or do not exist, but where they intersect, or can be made to intersect with others. In which arenas can they positively contradict each other? In which public or semi-public environments can this discursive confrontation take place? I’m interested in such cultural, aesthetic, or political frictions. What forms can aesthetic resistance or alternative take? That to me is the cultural realm, and not the well-mastered but non-challenged paradigms of style or narrative. This applies to commercial fields as much as the so-called Independent sector.

To make retail spaces look more private was a strategy that tried to defy generic interiors as soul-less symbols of capitalism. Pot plants, table tennis, and slouchy seating have now moved into galleries, boutiques, shops and hairdressers, which disguise themselves as private and personal spaces. Before: private flats presented in exhibition-like arrangements. After: retail spaces dressed up as private retreats with many personal touches and quirks.

Such instabilities of interpetation can potentially be interesting. However, these specific examples are mere differently configured sales points. Their informality represents now not an anti-establishment rhetoric anymore, but a quaint form of permanently self-regenerating, self-optimised contemporaneity.

We have reached – in terms of visual languages of the various markets (also of what we have previously called sub-cultures) – a high level of diversification and specificity of styles that are re-affirming customer profiles. However, this form of globalised (design) professionalism is draining public spaces (in big Western and Eastern cities) of the visual heterogenity and disfunctionality that it paradoxically needs to stay culturally fertile.

“I experiment with forms of teaching – or the generation of knowledge and its distribution. This is ‘Speed-Teaching’, a format in which roles are reversed and students become teachers and vice versa. It’s a great emancipatory and fun way of sharing knowledge. I’ve done it in different variations in London, Leipzig and Bratislava. It borrows its setting, as the name suggests, from speed-dating.”

In the same essay, you state that “The degree of critical reflection within graphic design has increased enormously over the period of the past twenty years. The discipline has changed for the better; its awareness of its own history has sharpened. Graphics is referencing itself eloquently. What is missing is a smart and sophisticated (semi)public reception and review culture. And this is precisely where the opportunity sits: to shift the notion of innovation away from an aesthetic exploration of form, towards the raising of the debate about relevant contents – and production of actually relevant contents.”

However, between the imagined past, the experienced past, and hopes for the future lays the very precarious present in which we are enthralled in entertaining and being entertained so much so that we are losing our ability for discussion beyond 140 characters per Tweet. As writer and artist Martha Rosler has succinctly put it, “Celebration and lifestyle mania forestall critique; a primary emphasis on enjoyment, fun, or experience precludes the formation of a robust, exigent public discourse.” Reasoned criticism has been supplanted by the medium.com pseudo-op-ed piece (sans editor, publisher, or suitable publication), the Facebook post, and the ever-expanding lifestyle publication (e.g. The Sunday New York Times having morphed from a news publication into essentially a self-contained style section with a thin news wrapper).

In a way, the increased sense of design’s historicity could be viewed as edu-tainment…

Yes, it’s true: it takes often longer to re-work, improve, check, proof-read and edit a text, than writing it in the first place. But that process is turning it eventually valuable source. The same could be said about a sequence of pictures etc.

It is increasingly hard to pursue a more time-consuming form of contents production since the contents can not only be “published” (90s desk-top-publishing basically meant instant production), but also broadcast and immediately distributed.

Truths produced by academia, or a discourse-dominated art scene, as desirable as they might seem, must be challenged just as much as the digital advertorials that are many of these blogs. It is precisely their repetitive and affirmative nature, and the inability for genuine entertainment that you can find in both of them.

Most style-blogs are just shopping-channels for teenagers on the internet. Yet Hollywood also eventually fed off a generation of movie directors that had initially learned their trade as directors of commercials or music videos, like Alan Parker or David Fincher. We’re in the middle of finding out what kind of idiosyncratically sick (in the current ambivalent interpretation of that word) literature a generation of narcissistic lifestyle-bloggers can produce. Provided some curiosity and the amusement that is artistic criticality… I’m definitely curious.

People want experiences, whereas the geezers of yore wanted excitement. The contemporary populace wants their H&M, their Disney/Time-Warner-controlled NYC-theme park Union Square, their simulated city-as-entertainment/shopping complex, smooth English language transactions at exotic tourism destinations replete with Thai and Mexican food options, an Oculus Rift forever within arm’s reach, and the absolute right to broadcast whatever they want to say whenever they want to say it without thinking about it too much.

Hence the desperate, and sadly doomed, desire for what middle-class people consider “authenticity”. The German playwright René Pollesch, whose plays have curiously combined a critical dissemination of dreams and failures of an educated and cultured class, talked about how him and the actors and actresses been using “authenticity” as a (playfully) derogatory term in rehearsals: “You authentic cow!” That makes complete sense to me. His externalized inner monologues, played out by the characters, are as hilarious and entertaining (!) as they are profound and telling – witnesses of how we try to negotiate our feelings and plans through language, symbols and actions. With layers and layers wrapped around the fiction of a “real me”, this phantasma of authenticity, which is supposedly hidden somewhere inside. Art is freedom, the opposite of authenticity.

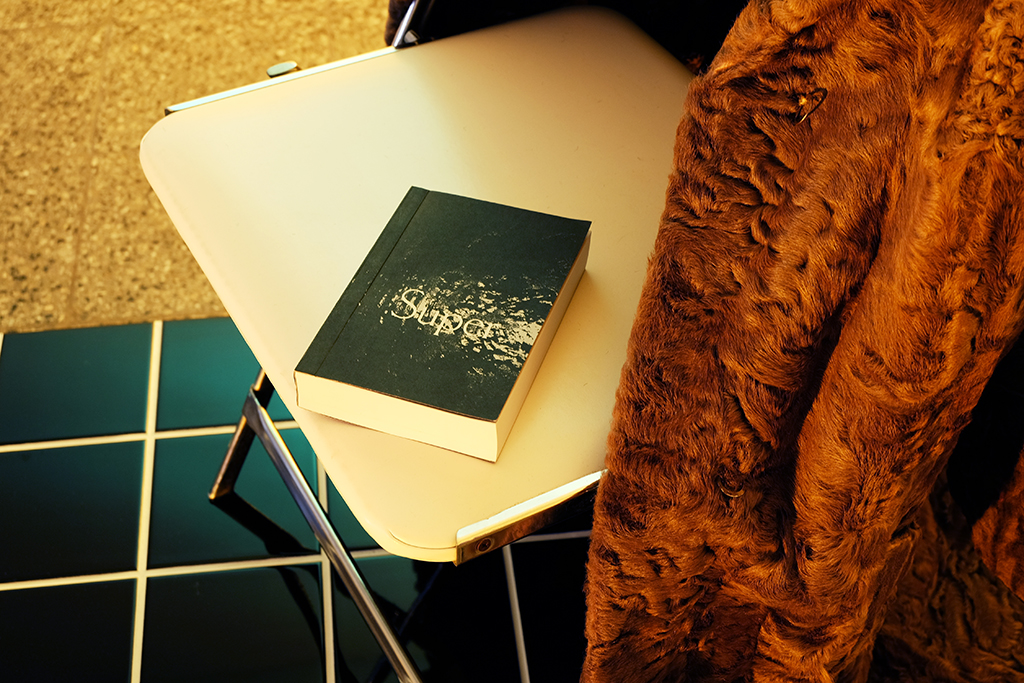

“This is a book which I conceived which does things a bit differently. I invited 50 friends, colleagues and students to translate and interpret the novel “Super-Cannes” by JG Ballard together, from English into German. It is a collective transformation of text, linked to the genre of artistic re-appropriation and cloning. It is an attempt to create temporary or partial collective authorship, instead of a singular. What you see on the pictures is the installation for distribution event, in which we relate the physicality of the book with some references to the book’s plot and it’s neoliberal creative elite topics.”

What kind of goals and outcomes (or lack thereof) do you perceive as being the most valuable for creative sectors of production, namely graphic design given contemporary circumstances?

I’ve always found the motto of (the aforementioned) Cedric Price very helpful: “Doubt, Delight and Change.” I do think that the transformative aspect of art and design is exciting, and that does include also “experiences”. If experiences include the possibilities of the production of arguments, and if not the possibility of resistance, than perhaps the production of counter-objects, to borrow an idea by Alexander Kluge and Oskar Negt. I suppose, graphics needs not just to redefine our traditional notion of the graphic objects, but also the possibilities of it being something else than just a vessel or commodity.

Currently I’m quite interested in the criticality that can be taken from the arts and the often dismissed traditional decorative arts, and how this can become part of a design practice that is invested into relationships of institutions. More specifically, I’m trying to research and develop design approaches that relates directly to strands of “Institutional Critique” [a by now historical strand of fine art that engages with the political and economic frameworks in which art is produced, presented or distributed]. How can design be both more sensitive to the workings and relations of a non-commercial institution, how can the process within manifest themselves visually and physically? What alternatives are there to flexible, yet completely conventional graphic design identities?

What do you feel are the most prominent MacGuffins in terms of design education today?

I’ve only recently come across the notion of the MacGuffin in design terms, in Dan Hill’s text “Dark Matters and Trojan Horses”, published by Strelka Press. In this he’s describing how specific qualities within a design (i.e. of a building) can become an argument or powerful example, that allow to drive forward innovations or changes (or a plot, to relate it to the Hitchcockian origin). So he sees the narrative device of the MacGuffin as a device to built up momentum, I suppose, just as Karl Marx saw “revolutions [as] the steam-engines of history”.

I feel strongly about the rediscovery of fictionality in design and how this can be seen not only as a non-authentic and PR-minded strategy of misdirection – but a very important form of design that challenges and subverts graphic clichés and narratives. I think it is very exciting to test out and explore such potential in an educational environment. Difficult, but crucial.

In “Everybody’s Got to Learn Sometime”, you intimate a “somewhat provocatively optimistic idea of learning, for the arts as much as in life, as something that is deferrable – but ultimately inevitable”. When did you personally feel the inevitability of having to learn?

Oh, I think there is just a small window, probably during one’s studies, when one’s own confidence (and cockiness) let’s you feel that everything is possible at that very point. You just need to grab the opportunities, and kick some old guy, or girl, off that throne. In order to do the stuff, or project, you want to do. Learning at that point just seemed a only a means.

When I re-designed the course at the Leipzig Academy a few years ago I was already very much interested in that very process itself and the politics of learning (teaching) and so I was experimenting with various formats and forms of participation by the students in the programme, I had found Jaques Ranciere’s “Ignorant Schoolmaster” and his fable of the equality of minds very inspirational, both in practical and theoretical terms.

I guess, in this discussion we should also remember that this kind of learning differs from “acquiring new skills”. It seems to me that currently innovation too often is seen as a technology-driven concept. Learning also needs sometimes the complete absence of skill, craft, and even ideas. Some leeway for “Genial dilletantes”. And being not ingenious is also a perfectly viable option we mustn’t disregard…

Understood. Thanks very much, Oliver!

With that, the latest installment of “Huh?” and the very first of 2017 screeches to a halt. Stay tuned for more!best Running shoes | Nike News