This post is a transcription of a brilliant lecture by VCFA faculty member Ziddi Msangi about his visual research and exploration of the form and meaning of the African garb, kanga.

Today I would like to talk to you about a form of visual communication called the kanga.

I will describe what the kanga is, including its structure and history. I will then explain how it is used as a form of communication in traditional moslem society and within the different communities in East Africa. We will look at the type of messages contained on kangas by viewing a representative sample. Look at the advantage of pattern and text recognition for communication in a country with over 130 distinct language groups, and finally look at the visual outcome of this research as work created during my sabbatical leave in 2011.

This presentation relies on information gathered from primary and secondary sources. I am indebted to my family members who patiently allowed me to interview them by phone, the Erie Art Museum collection of Kangas, the field research in Tanzania of the German scholar Dr. Rose Marie Beck, the field research conducted in Zanzibar by Tanzanian scholar Dr. Rose Ong’oa and the field research conducted in Kenya by Phyliss Ressler.

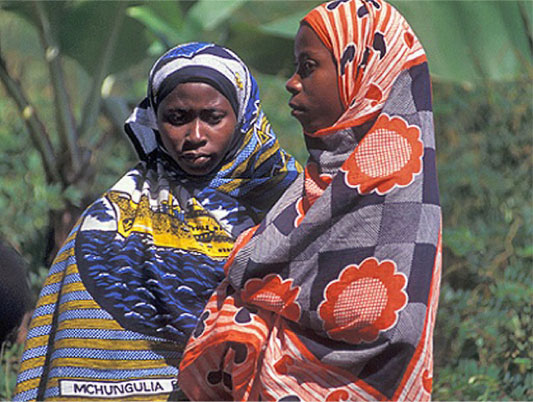

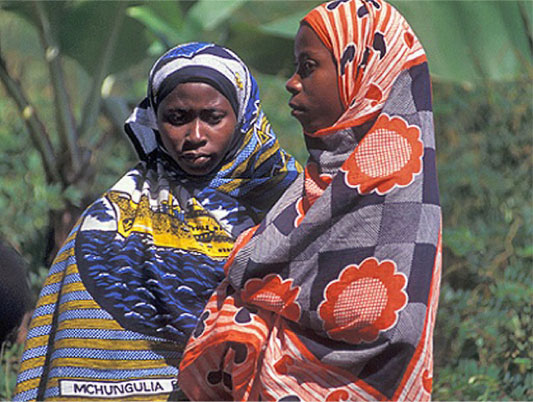

Throughout East Africa, but especially in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda, women wear wraps called kanga. They are a colorful garment that adorn women of all ages, in the village or the city, at home or at market.

My interest in this particular topic came about thru a pursuit of creative writing during a sabbatical leave.

While writing, I found that as I constructed an image, inevitably the kaleidoscope of colors that came to mind were of the kangas from my childhood.

I grew up seeing Kangas everywhere. Even during the many years my family spent here in the US, the Kanga was a central part of my mother’s wardrobe. It covered tables at times, as a makeshift table cloth. It was the wrap she threw on after arriving home from work-a sign of her role as mother and wife to my father. In all my imagery, as I try to recall the sights and spaces of childhood and of East Africa, Kangas are present.

Swahili woman wrapped in a kanga (from Cicely Peace Matunda)

In a traditional hierarchical social structure where there are prohibitions against women engaging in “bad talk” including gossip, speaking out of turn and shaming, kanga are used as a way of circumventing these restrictions. This lecture explores the intersection of private and public space these garments inhabit when women wear them and their evolution as a distinct form of visual communication.

For the purposes of this lecture, I am framing the kanga as a form of visual communication, where communication is understood as social interaction , and here I borrow from the German Scholar Rose Marie Beck: “Communication is understood as social interaction, whereby the focus is not solely on meanings in a pragmatic or semantic sense, but rather on social meaning–the negotiation of relationships between the interactants in an area of tension between individual, social and cultural interests.”

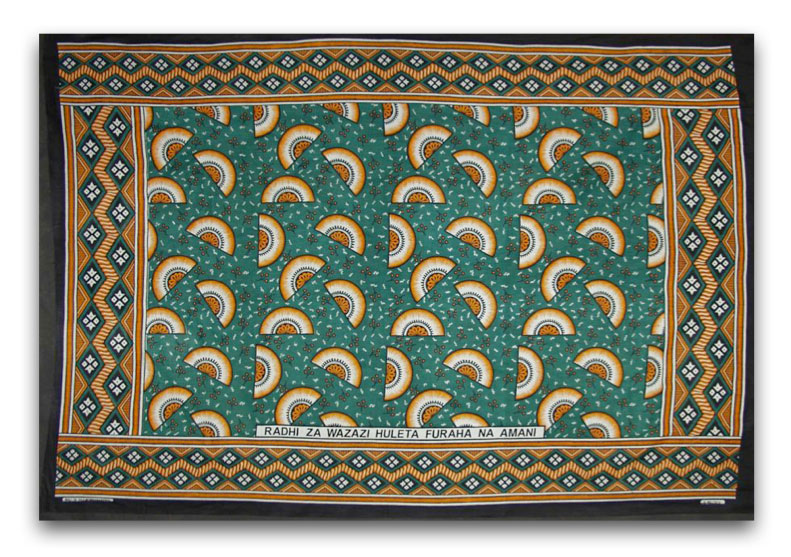

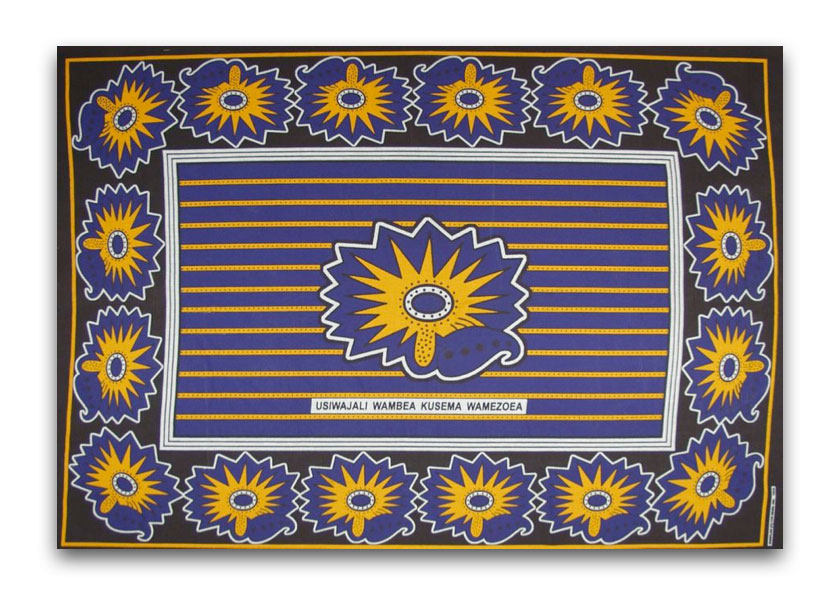

“Gossipers will never stop; don’t pay them any attention” – 100cm x 150cm from the Erie Art Museum collection

What is a Kanga

Kanga’s are cotton fabric wraps screen printed, typically in three colors. They measure about 39 inches x 59 inches (100 cm by 150 cm). They are produced in Tanzania and Kenya for the domestic market as well as imported from India and China. Kangas are worn by women and girls in both public and private settings.

An exception to this rule, is that at home, men may wear kangas as a temporary wrap, similar to wearing a towel around the waist.

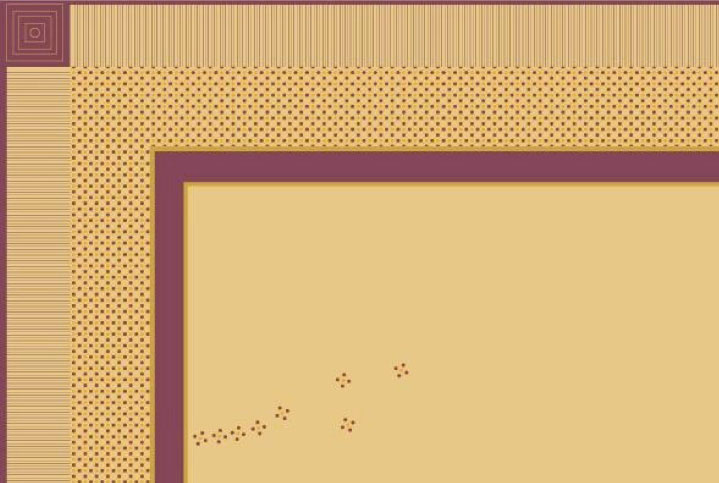

The structure of the kanga consists of three parts:

- a patterned border (called a pindo)

- a central design (called an mji)

- and a saying or proverb in swahili set as type in a box above the bottom border. This is called the jina.

Kangas can be bought at market or in stores that sell kangas. They are cheap to own, and usually sold in pairs. In 2012 the going rate was 8,000 tsh for a pair ($4.70).

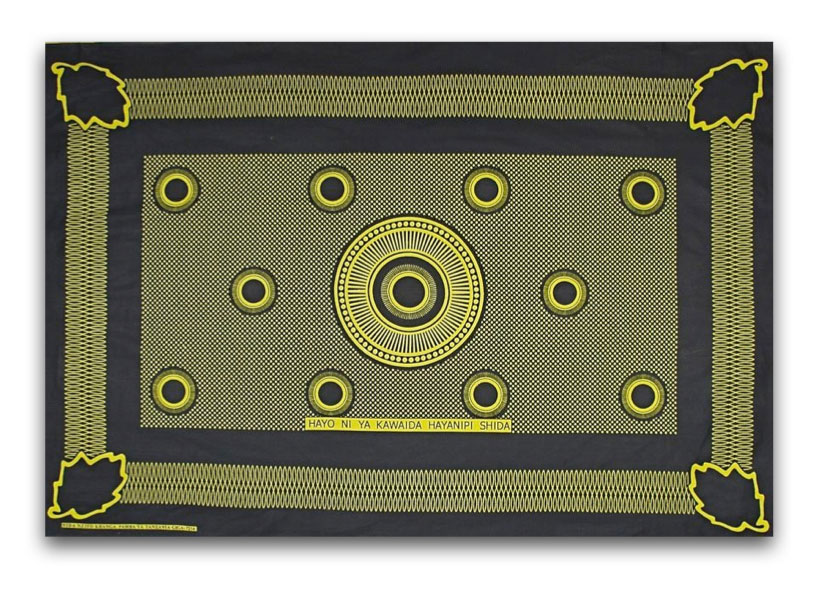

“This is normal for me, I’m not bothered by it.” – 100cm x 150 cm from the Erie Art Museum collection

Thesis of how it is used as a form of communication

The messages on Kangas range from proverbs, to political slogans and words of wisdom. Women give and receive kangas as gifts. How one decides on what kanga to purchase is not only an aesthetic decision, but also a decision that takes into consideration the message contained on that particular kanga.

There are established conventions that determine the color of kangas used for special occasions–such as a wedding. But most kangas are chosen based on the pattern and message. Even though most kangas are purchased by women for themselves or for another woman, Kangas are also given to women as gifts by males who are close to them, typically a husband. They can be seen, in some settings, like a really special greeting card, but more enduring in that they are worn on the body and may be displayed publicly.

Origins in Tanzania and East Africa

The origin of the Kanga is attributed to the Swahili people on the island of Zanzibar. Zanzibar is now a part of the East African nation Tanzania, which was formed in 1962 as a union of Zanzibar and Tanganyika. Tanzania is located on the East African coast, south of Kenya and Uganda.

Phyllis Ressler writes in her paper “The Kanga, A Cloth That Reveals: Co-production of Culture in Africa and the Indian Ocean Region”:

“Many of the symbols used in the Kanga have roots in European, African or Indian Ocean culture. This was confirmed both through interviews with designers of Kangas and reviews of the sketch and sample books compiled by the printing houses of europe. The symbols on Kangas can be found in 18th century English wallpaper books, French tapestries, ancient Persian carpets and African ceremonial garments or objects. They can be found in woven cloth from the Middle East, as shapes of local fruits and flowers, and as ancient Indian tie dye designs. All masterfully woven into a mix of color and life.”

Tanzania has over 130 different ethnic groups, each with a distinct language. Kiswahili was adopted as the national language during independence from Britain because of it’s widespread use as a trading language.

The Swahili are an ethnic group located along the coast of Kenya, Tanzania and on the island of Zanzibar.

Kiswahili is a language (“ki-“ meaning “of the Swahili”). Swahili culture has been highly influential throughout Tanzania– defining the national language, and influencing the food, religion, customs and clothing of all the ethnic groups that inhabit Tanzania. The kanga is one visible manifestation of swahili culture.

Throughout this lecture, when talking about Kanga, I will be describing the culture and customs of both the Swahili people and observations from my own ethnic group, the Pare.

Zanzibar and it’s people, the Swahili, are born from a complex history of the Arab conquest of the East African coast during the 17th and 18th centuries and the trade in slaves that occurred until the late 19th century.

Based on the field research Dr. Rose Ongoa conducted in Zanzibar, the original kanga evolved from the plain white cotton wrap slave women would wear. As they were liberated they imitated the garments that free women wore by decorating them with similar patterns. The woman on the left wears the common garment while the woman on the right wears a hand painted wrap that has a border design similar to the imported Portuguese handkerchiefs that were popular among the ruling class.

Free women Posing in Hand Painted Kanga (Late 1800s from Zanzibar National Archive – Images of swahili women Compliments of Zanzibar National Archive, AV 31.62)

According to Rose Marie Beck:

“The Kanga played an important role in the emancipation of slaves and their integration into the Muslim, Swahili community. As a symbol for their emancipation it referred both to their ‘new” status as members of this community and at the same time to their descent from the former slave population. The patterns, for instance, were inspired by the precious needlework of rich and patrician women. By wearing such a Kanga, a woman could indicate her knowledge of culturally important patterns and taste and assert her integration into coastal society. On the other hand, these patterns were not the ‘real thing’ and thus referred to her new status on the bottom end of social hierarchy. These processes were made visible on the Kanga, at the same time the Kanga itself was part of these processes in which social affiliation and power were negotiated.”

Kanga from this period did not have text, animals or depictions of people on them. The kanga shown here were hand painted in the style of the imported portuguese handkerchiefs. As the decorated kangas became more popular, block printing was used to increase the numbers that could be produced. They continued to grow in popularity. The british began importing screen printed kanga in the early 1900’s. These came from textile factories from Britain and India.

In the 1930’s text begins to appear on the kanga.

According to Dr. Ongoa:

“Kanga texts originated in the 1930s, when Haji Essak Abdulla Kaderdina, a cloth trader in Mombasa, Kenya learned of Zanzibar women’s love of proverbs and their preoccupation with establishing a foothold in Swahili society. Seeing a market opportunity, he began printing a motto or proverb on the border of the cloth.”

The language printed on kangas from the 1930 to the early 1960’s was arabic. After the main land of Tanganyika gained independence from Britain and formed a united republic with the island of Zanzibar, kiswahili replaced arabic on the kanga.

The behavior of women in many East African communities is constrained. This is a result of patriarchy and a hierarchical social structure, rooted in an agrarian society. Traditionally, women in swahili moslem society are prohibited from engaging in “bad talk” which would include gossip and shaming. They must speak in soft, low tones, be polite, and be deferential to elders.

The sayings printed on kangas express feelings and opinions that would be frowned upon if spoken aloud. Through the kanga, moslem women challenge societies guidelines for behavior yet remain within the tenets of their faith.

Case Study number 1:

Ataka yote hukosa yote

Who wants all, loses all

Rose Marie Beck’s case study from field work conducted in Tanzania:

“Ataka yote hukosa yote- Who wants all, loses all”. About fifteen years ago, Ms. Hafswa was given a kanga by her neighbor, Ms. Yasmin. it has the inscription “Ataka yote hukosa yote- Who wants all, loses all.” Ms. Hafswa got very angry and went to confront Ms. Yasmin and ask her why she gave this particular kanga. But Ms. Yasmin denied a communicative intention by saying that because she was illiterate she didn’t know the meaning of the inscription. Ms. Hafswa did not believe Ms. Yasmin, because it is common knowledge that even illiterate women take part in kanga-communication. But she had to retreat, fuming and with feelings of utter impotence and loss of dignity.

The incident occurred shortly before Ms. Hafswa separated from her husband, a distinguished member of the community. WIth the gift of this kanga she felt that the blame for the breakdown of her marriage was put on her, but also that people gossiped about her. She saw this gift as an unjustified intrusion into her privacy, and also that the other woman had probably been jealous and was now rejoicing at what she saw as her failure”.

Case Study number 2

Nyumba yenye upendo haikosi riziki

A home that has love will be bountiful

The following is based an interview I conducted with Prof. Namkari Mziray:

In my conversations with Prof. Mziray, I tried to get her to relate any stories or observations where she witnessed communication between women using the kanga as described in the previous story. She didn’t have any. I thought at first that it might be modesty, maybe this wasn’t something one discussed with a man. But that wasn’t it. No, she related– Someone might wear a kanga that says “don’t gossip about me” but for her and her circle, they just said what was on their mind. That the power dynamic was different and the restrictions for women in her position were not as pronounced.

Which brings up another point; Kangas would be more common in coastal communities or in the village but as you move into urban spaces it can also be a signal for class.

Prof. Mziray recalls that as a girl she only wore Kangas to fetch water when she was visiting her grandmother in the village or when going to the market as a way to appear more modest.

“nyumba yenye upendo haikosi riziki” – ceremony of mother receiving kanga’s at wedding and kanga dress

Another context that you will see Kangas are at big public ceremonies such as weddings or funerals.

At a wedding, there is a ceremony where the mother in law is wrapped in Kangas. Since her daughter is leaving, the idea is she will be feeling cold, so to comfort her, to get you ready when the parents come.

Prof. Mziray then paused, and remembered a kanga that her daughter received during her wedding.

The message was “nyumba yenye upendo haikosi riziki”– “a home that has love will be bountiful”.

Of all the Kangas that her daughter received she wanted the message of this one to resonate, and so she took the kanga to a seamstress and had a dress made from it with the message prominently featured on the side of the dress where it would be visible. She wanted to communicate to the daughter and husband to pursue love and not material wealth, to assure them that all would fall in place.

Case Study number 3

msinionee wivu

don’t be jealous of me

The following is based on a narrative my cousin shared with my sister, who shared it with me:

On the occasion of the homecoming of the Prime minister of the country when he returned to our village, my cousin observed the following message on the Kanga worn by the prime minister’s wife as she emerged from her husbands limousine:msinionee wivu

don’t be jealous of meThe event was attended by people from the village, thus the prime ministers wife’s deferral to wearing a traditional costume rather than western attire.

“My son, concentrate on your studies. Don’t fall into the trap of worldly things.” – 100cm x 150 cm from the Erie Art Museum collection

The following images from this section are from the Erie Art Museum collection: Kanga and Kitenge: Cloth and Culture in East Africa.

Rose Ongo’a makes the following observation about swahili culture and the wearing of proverbs:

“The Swahili love proverbs and consider polite speech a prerequisite of competency in Kiswahili. An individual’s ability to use tactful speech in strategic situations is a mark of intelligence. Women masterfully take advantage of proverbs and euphemisms as gentle yet powerful means to admonish others– while earning respect from peers as competent, intelligent speakers of Kiswahili.”

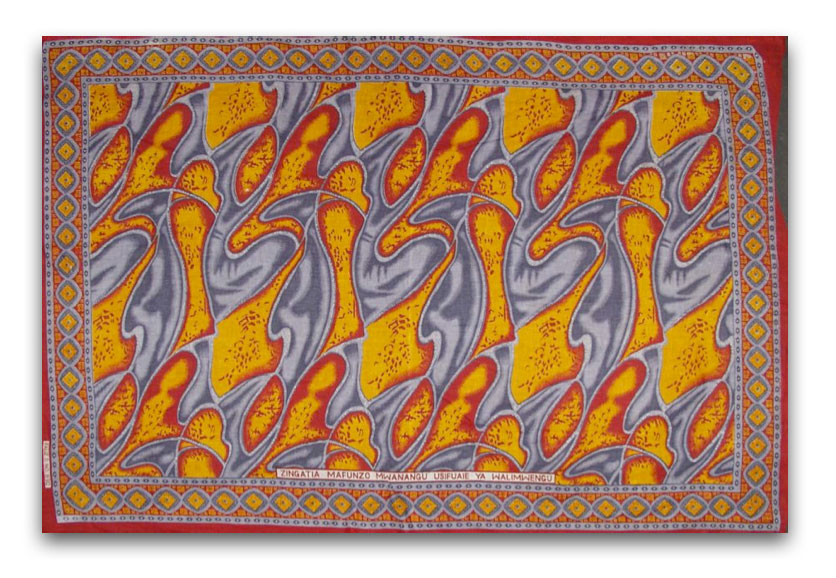

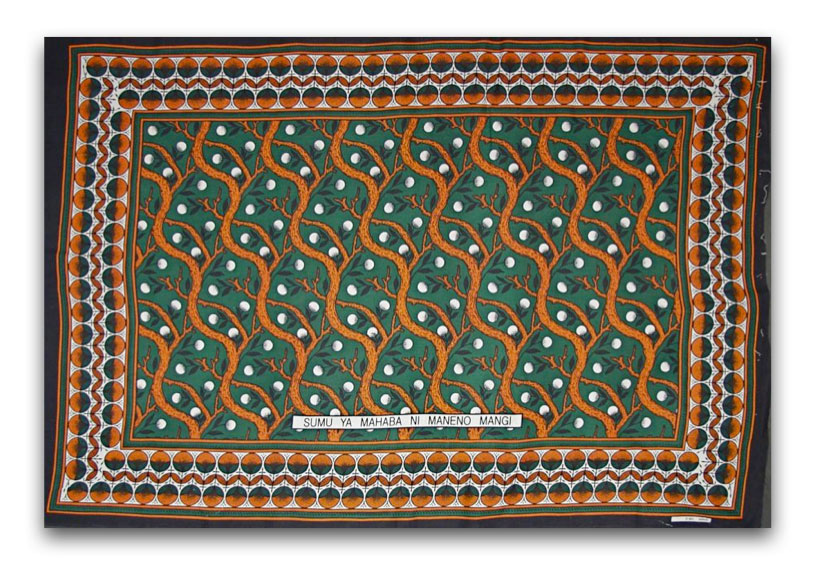

“You can poison romance with too many words.” (In English this translates, “Watch your mouth!”)- 100cm x 150 cm from the Erie Art Museum collection

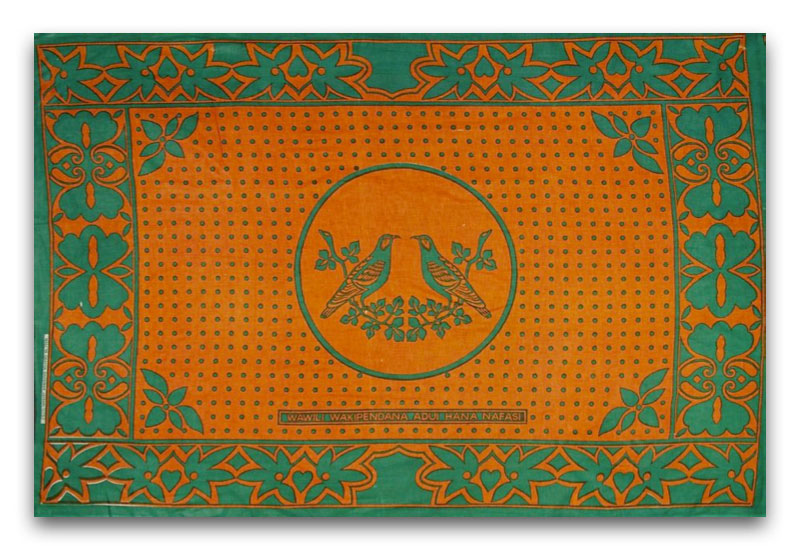

“When two are in love, their enemies can’t hurt them.”- 100cm x 150 cm from the Erie Art Museum collection

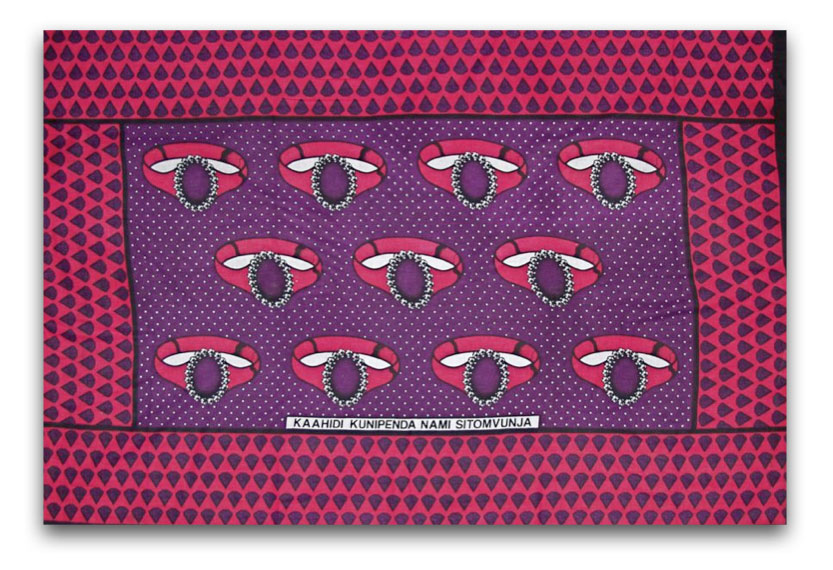

“He has promised to love me, I won’t let him down.”- 100cm x 150 cm from the Erie Art Museum collection

“If you won’t care about me, I won’t care about you.”- 100cm x 150 cm from the Erie Art Museum collection

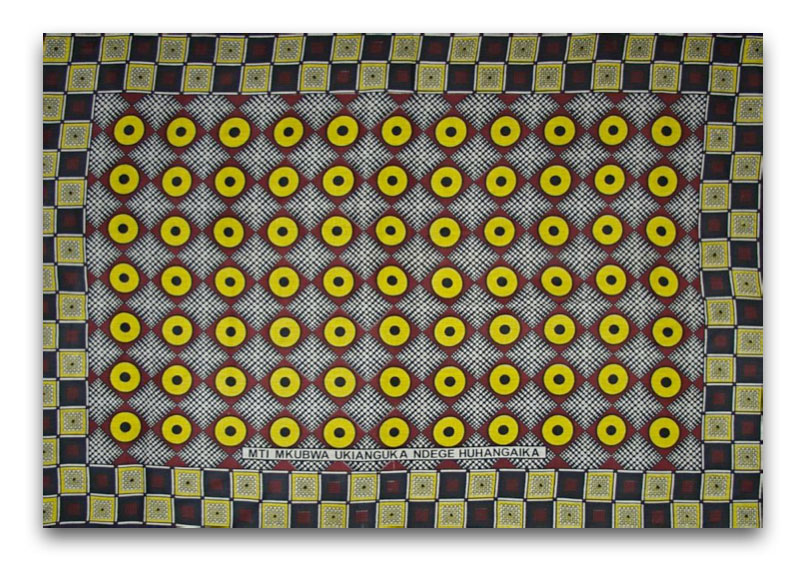

“When a big tree falls, the little birds are in anguish.”- 100cm x 150 cm from the Erie Art Museum collection

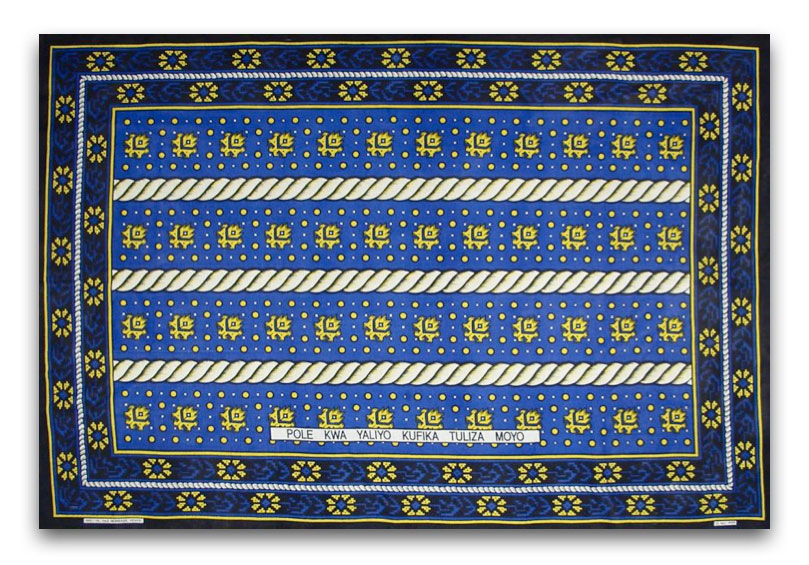

“Sorry for your loss, we hope your heart can find peace.”- 100cm x 150 cm from the Erie Art Museum collection

“To the eyes a native, to the heart, a stranger.”- 100cm x 150 cm from the Erie Art Museum collection

Pattern recognition

Dr. Rose Marie Beck makes a compelling argument for the framing of the kanga as a communicative sign in her article:

Ambiguous Signs: The Role of Kanga as a Medium of Communication:

“One of the prerequisites of a code is that it contains signs that form a socially shared system” in this case it is the kanga. the sign Kanga consists of a pattern and an inscription which are allocated to each other (both are printed in cloth). The pattern and motifs taken for themselves may be interpreted on their own… The inscription, on the other hand, is in itself a sign insofar as the sounds of a language are transcribed visually into letters. And the language, in turn, forms a system of signs, too. Two complex signs in their own right-pattern and inscription- are combined to form another complex sign.”

The relationship between the pattern and inscription are arbitrary so it is a highly unstable system. Also there are a tremendous number of kanga in the general population, as new designs come out every month.

Women read the text and memorize it as associates with a certain pattern. So in passing, one may know the message contained on a kanga without necessarily being able to read the inscription on the kanga.

The Sabbatical Show

During the Spring of 2011, I was granted a sabbatical leave. One of the requirements for granting me the leave, was a clearly defined set of goals and objectives—what are you going to do, and how are you going to do it.

My proposal for the leave was to create a series of posters with the theme: Liberation and Independence—Retracing the Narratives That Form Identity

It read:

“There are a confluence of voices that gather around and speak to me, framed in memories and stories, habits of behavior and legacies still unfolding. I am trying to distinguish one from the other, listen to each distinct pitch and tempo. Thus origins, beginnings, allegiances, obligation are the starting point of retracing the narratives from Tanzania, Kenya, Oakland–African, and American voices embodied in Nyerere—the first president of Tanzania, Kenyatta–the first president of Kenya, Senator J. William Fulbright–the founder of the scholarship that brought my family to America in the 1970’s, The Black Panthers, Malcolm X, Christianity and Buddhism.”

I spent the first few months, writing and spinning my wheels. A series of personal crisis put the project on the back burner; I was warming over ideas, but nothing was really cooking.

The form of the poster seemed to be a stumbling block. What were the posters for? Who was the audience? How would my narratives work in a poster, and would the posters have to be viewed in sequence in order for them to make sense?

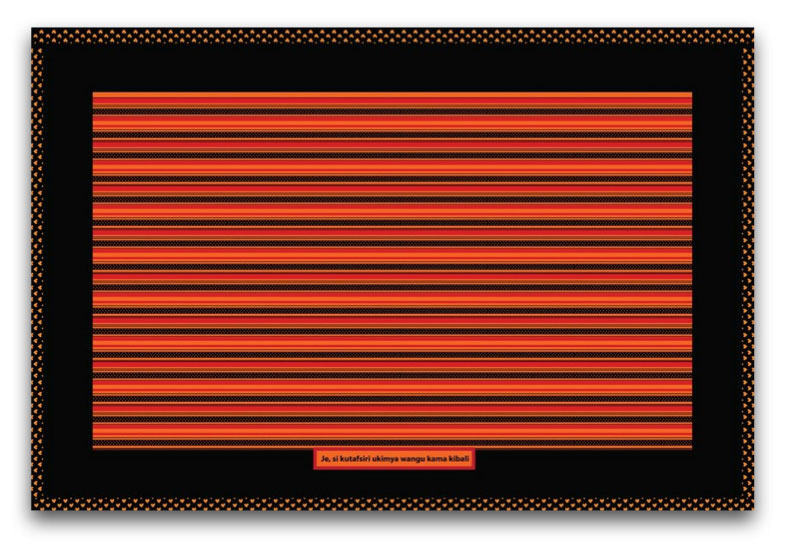

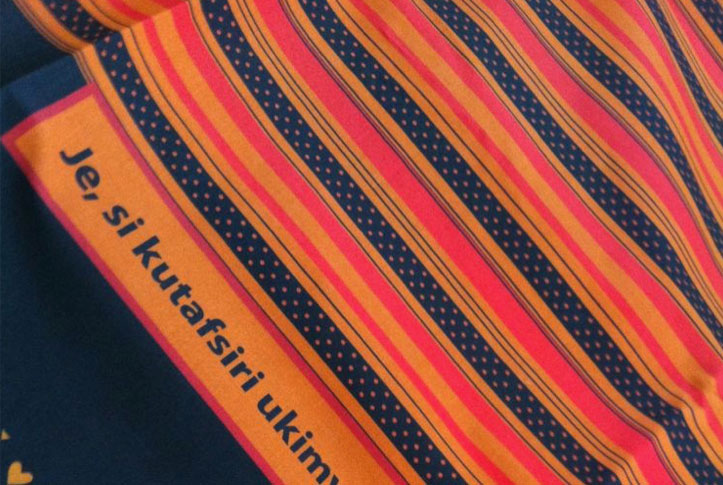

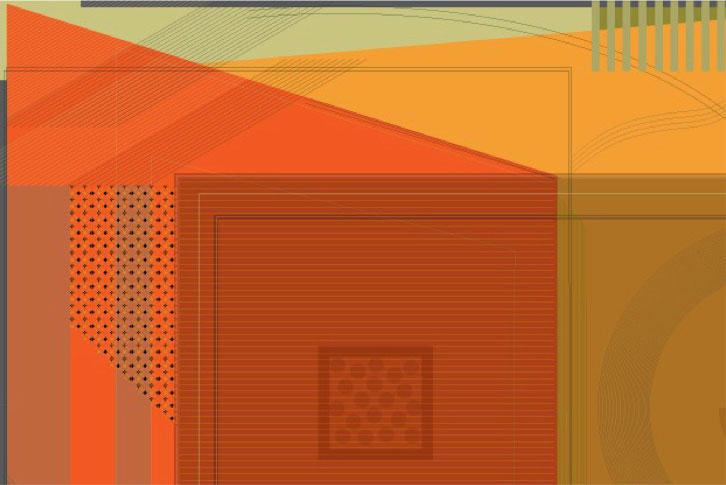

“Je, si kutafsiri ukimya wangu kama kibali” / “Do not interpret my silence as approval” – 100cm x 150 cm from UMass Dartmouth sabbatical show 2011

“Je, si kutafsiri ukimya wangu kama kibali” / “Do not interpret my silence as approval” (detail) – 100cm x 150 cm from UMass Dartmouth sabbatical show 2011

This was the first Kanga in the series.

This text is about the negotiation of power in communication. I invoked the divine feminine, getting in touch with that side of myself. Silence is not necessarily acquiescence.

With the form, I was teaching myself how to create repeats and patterns in Illustrator.

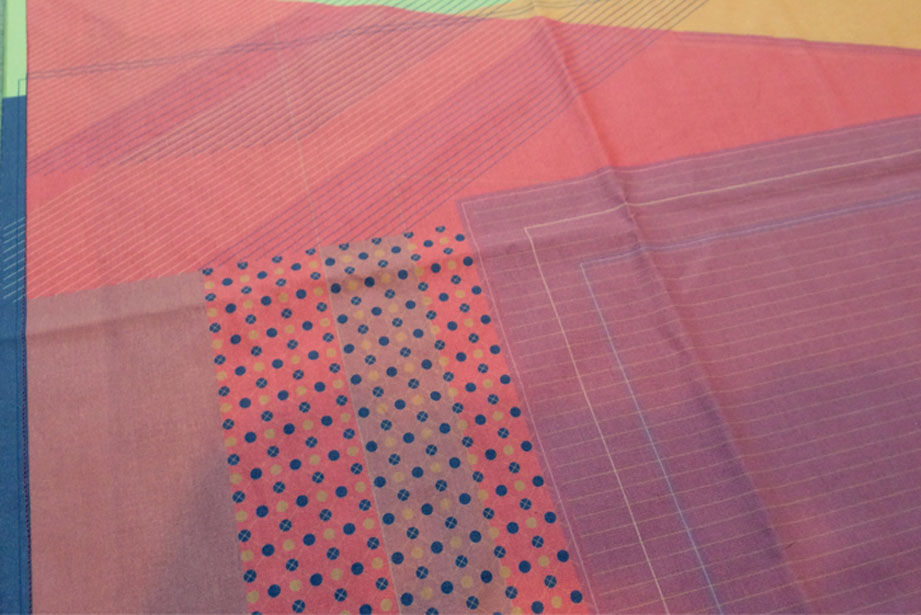

Another Kanga in the series was based on a theme I was exploring during the Summer of 2011.

The subject is the East African Carrier Corp—Africans who were coerced into the service of the British army during the first world war to carry supplies in military campaigns, including Europe.

My interest in the subject, was a result of my curiosity about a word I encountered in Kenya, Tanzania, and Ghana: Kariako. I grew up with the word Kariako, and always assumed it was a Swahili word for “Big Market” as there was a Kariako in Nairobi, Kenya where my parents lived and others in Dar Es Salaam and Arusha, Tanzania. It wasn’t until 2002 while traveling in West Africa that I heard the main market in Accra, Ghana referred to as Kariako. I realized that it wasn’t a Swahili word.

My research revealed that the word Kariako is the way Africans pronounced the English words “Carrier Corp”. The market, it turns out, was the assembly space throughout the British African colonies where conscripts gathered before marching off to war. Over time the spaces became associated with the regiments that departed from there, many never to be seen again.

“Ushirikiano wangu atakuja kwa bei” / “My cooperation will come at a price.” Carrier Corps 1914-1918 – 100cm x 150 cm from UMass Dartmouth faculty show 2012

With this piece I am hinting at the coming independence movements later in the century, largely influenced by Africans who traveled abroad and returned home to lead the independence efforts.

“Ushirikiano wangu atakuja kwa bei” / “My cooperation will come at a price.” Carrier Corps 1914-1918 (detail) – 100cm x 150 cm from UMass Dartmouth faculty show 2012

The background texture is composed of coffee beans, one of the many cash crops cultivated in British colonies.

“Kwa nini kukimbia wakati unaweza kutembea” / “Why run when you can walk.” – 100cm x 150 cm from UMass Dartmouth sabbatical show 2011

“Kwa nini kukimbia wakati unaweza kutembea” / “Why run when you can walk.” (detail) – 100cm x 150 cm from UMass Dartmouth sabbatical show 2011

“Kwa nini kukimbia wakati unaweza kutembea” / “Why run when you can walk.” (detail) – 100cm x 150 cm from UMass Dartmouth sabbatical show 2011

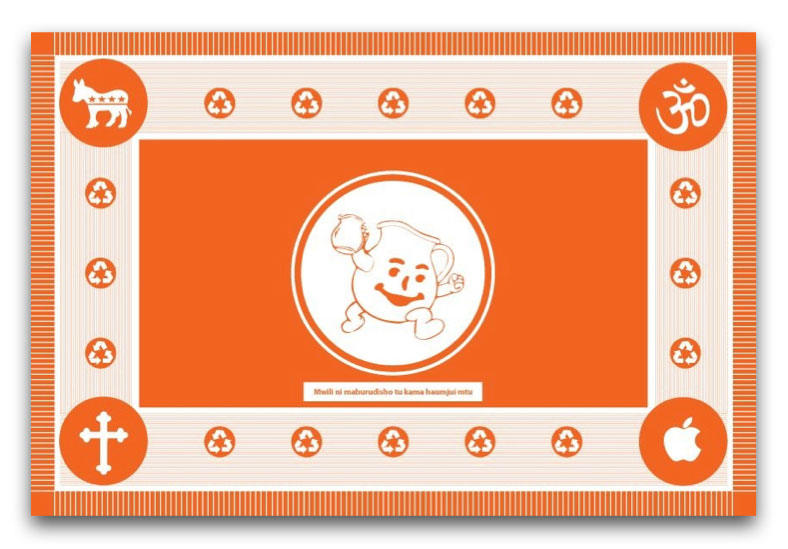

“mwili ni maburudisho tu kama mtu hajui mtu” / “the body is just a distraction if one doesn’t know the person” – 100cm x 150 cm from UMass Dartmouth sabbatical show 2011

Originally this piece was conceived as a judgement of all the extremist positions people take and the conviction with which they hold to what seem to be opinions or preferences but not absolute truths. As I started sorting through what positions I would represent, I found myself growing uneasy with my relationship to the subject. My partner challenged me to consider turning the eye inward. To confront my own ideologies and convictions.

The symbol in the upper right is the Om (or Aum). This is a Hindu symbols and its sound is used in meditation. In Hinduism, the word “Om” is the first syllable in a prayer and used to symbolize the universe and the ultimate reality. Some people say that this symbol represents the three aspects of God: the Brahma (A), the Vishnu (U) and the Shiva (M).

“mwili ni maburudisho tu kama mtu hajui mtu” / “the body is just a distraction if one doesn’t know the person” (detail) – 100cm x 150 cm from UMass Dartmouth sabbatical show 2011

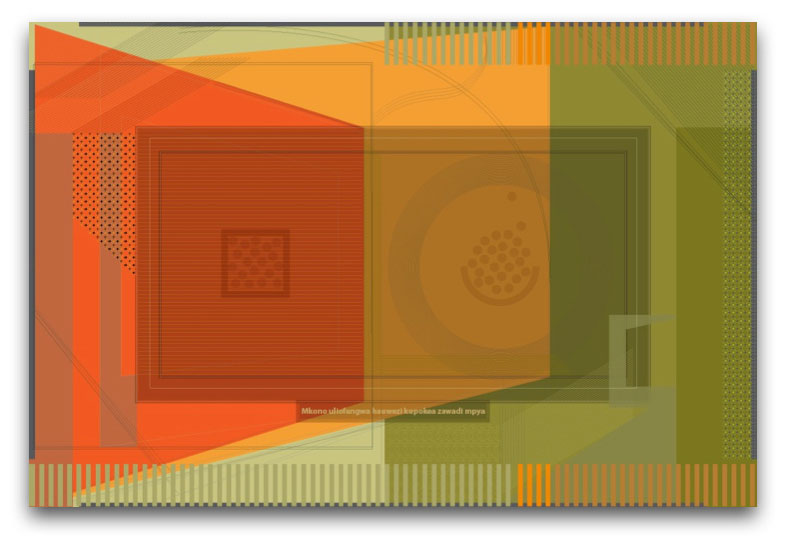

“Mkono uliofungwa hauwezi kupokea zawadi mpya” / “a closed hand can’t accept new gifts” (detail) – 100cm x 150 cm from TaDa! show 2014

“Mkono uliofungwa hauwezi kupokea zawadi mpya” / “a closed hand can’t accept new gifts” (detail) – 100cm x 150 cm from TaDa! show 2014

“Mkono uliofungwa hauwezi kupokea zawadi mpya” / “a closed hand can’t accept new gifts” (detail) – 100cm x 150 cm from TaDa! show 2014

Conclusion | Asante | Thanks

“Kangas can be found all over the world. Japan, Lamu, the Rift Valley, Nairobi, Dar es Salam, the Comoros islands, Mozambique, Eastern DRC, Oman and Dubai are but a few of the locations where kangas have been worn and used for generations. In each place the role of the Kanga is shaped by culture and local use.”

(Ressler)

In conclusion, we can appreciate the complex history that created the kanga and the ingenuity of the human spirit to find ways to make meaning and and find expression.

For me, remembering and reforming have become somewhat sacred acts predicated upon the understanding that with our considered evaluation of the past and those whose stories we rely upon, we are participating in a continuing ritual of recovery and interpretation.Sport media | Real Talk: adidas Stan Smith, Forever – Fotomagazin