My Korea Study: Gender, Race, and Language in South Korea

Gender

In March of 2013, I came across a “glass-ceiling index” that The Economist had complied to show where women have the best chance of equal treatment at work. (You can find the complete report here.) Based on five indicators across 26 countries, New Zealand scored highest on the average (close to 90 out of 100). South Korea scored lowest at approximately 14 out of 100. These numbers can be subjective and their accuracy can be debated. But there is something to be said when my personal life experience has told me that “Korea is a very hard place for women” to be matched with a 14 out of 100 score. The satisfaction of an acknowledgement and the glee of the affirmation was soon to be followed by the sorrow of what the reality has been and is for the women in South Korea.

I recall a joke I frequently heard when I was growing up in Korea. 북어랑 여자는 많이 때릴수록 맛있다. First of all, this joke refers to dried pollack. It is hard as a rock. To use it in cooked meals, it has to be beaten down to a pulpy consistency. The joke says, “the more you beat dried pollack and women, the better it tastes”.

There is another joke that I used to hear. It goes something like this: There are four kinds of men. 1. Smart and diligent, 2. Smart and lazy, 3. Stupid and diligent, 4. stupid and lazy. The point was to rank these four groups into who would make the best husband. At the top was 2. Smart and lazy. They are so lazy, but brilliant that they will come up with an amazing idea so that with the smallest effort you will be a millionaire. The worse husband will be 3. Stupid and diligent because they will get a job that takes so much effort, but never learn to leave it because they dutifully keep doing the work for little payment. The day I heard this joke I flipped it in my mind as to how it would apply to Korean women. Who would make the best bride? 3. Stupid and diligent. Who would make the worst bride? 2. Smart and lazy.

When I was 20 years old, I was having a big argument with my father (breaking the rule of piety in the world according to Confucius.) At one point my father turned to me and said, “you’re probably one of those FEMINISTS, aren’t you?!” I look at him and said, OF COURSE I AM. Claiming feminism was to me like a warm fire place on a cold day. It was like my first really good cup of coffee. It was a no brainer. Done deal. Equality? Check. Balanced dialogue? Check. Respect? Check. It turns out my understanding of what feminism is and how feminism is sometimes understood by the world were two different things.

When I started teaching at the age of 29 at a university in a small town in Ohio, I had one female student asking to speak to me after class. She was hesitant, but then asked her question. “You seem so nice… But, but are you a feminist?” I could not understand the context of her question. What did she mean by BUT are you a feminist? I soon learned of the anger and resentment associated with feminism and what was perceived as “male bashing” along with the term feminazi. It was like finding out about the evil twin I never knew I had.

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross introduced the concept of the five levels of grieving. When a person is going through a horrific experience they will go through multiple levels of emotions: Denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Perhaps American feminism at the time was perceived as going through the ANGER stage and so it had frightened many of it’s allies and foes. Anger can frighten anyone. A person who is openly expressing anger about what they are experiencing can make the best of us take two steps back. Let’s not confuse anger with a fundamental idea about equality. Feminism is having a “branding issue” in America. Somehow it is considered CONTROVERSIAL and SCARY and EXTREME.

Can we skip the ANGER part and get to the calm, reflective and articulate part? I’m sorry to say that we can’t seem to skip developmental stages. I’ve been known to have four out of these five stages to be on “shuffle and repeat ALL” mode for over a decade at a time. At some point we have to take charge of what we feel, what we see, and decide what we are going to do about it. Does acceptance mean defeat? Does acceptance mean giving up hope? Does acceptance mean that we are just going to wait to die? In my own personal experience, acceptance has brought clarity. (Even if you have to bring your sword with you sometimes.) What does acceptance look like to me? It is about bridging the two most radical parts of me: my head and my heart.

The head wants change NOW. The heart wants to be heard.

The head gathers evidence for the fight. The heart weeps for the crushing sadness.

The head knows how people can dig in their heels based on fear, or a misunderstanding. The heart knows change can be slow but recognition can be instant.

The head is up for a good fight. The heart desires peace.

The yin and yang of these two parts combined brings a strategy to the table that has patience imbedded into the process of evolution.

Do you believe that men and women should be paid the same amount of money for the same work? Then you might be a feminist. Do you believe that women and men should have access to the same opportunities and privileges? Then you might be a feminist. Do you believe that women and man differ in their gender identity, but they are the same in the fact we are human-beings? Then you might be a feminist. More people in America identify with the values of feminism, but do not identify as feminist. Feminism is having a “branding issue” in America.

If you are ever curious how you might be more of a practicing feminist, ask your partners, friends, colleagues and loved ones what they are experiencing. Ask them about all the invisible experiences that make them question their judgment. All the invisible experiences that make them question their reality and sometimes their sanity. Seldom do we want you to solve our problems. Mostly we want to be heard and acknowledged. That can be the beginning of something. But as Homer Simpson once said, “Just because I don’t care doesn’t mean I don’t understand” is a harsh reality that anyone who has experienced prejudice has come across. The solving of our own insufferable situations take time, persistence, and it is mostly a lonely journey. But knowing that there are peers out there, and people who are looking on with hope that you will get to the place that you desire can make all the difference.

Tradition. Fuck Tradition

My Korea is my South Korea, is my Seoul, is my Mother, is not my Mother, is my Grandmother. My Korea is about rejection, about pain, about surviving, about being ugly, about being stupid, about being a slave, about being a victim, about being a perpetrator. My Korea is about tears, about longing, about never being loved, about being hated as a woman, and never not quite a girl. In Korea, I am too tough, too severe, too loud, too opinionated, too fat. I am unlovable in Korea. So I reject you.

When Eli, my son, was born a month early in 2007, he was barely five pounds. He ended up in the NICU for body temperature regulation issues and I was confronted with the image of my new born baby with tubes going up through his noes and down his throat. Life is precious and vulnerable. In Korea, we celebrate the birth of the baby 100 days after they are born. This is most likely due to high infant mortality rates: not counting chickens before they have had a chance to survive the actual birth. This celebration is called 백일 (Baek-il: literally meaning 100 days). As Eli’s Baek-il was approaching, I started to think about the traditional rice cake you get for the baby. Up until this point in my life, my understanding of tradition was “a handy little tool to oppress and control people.” (Thus the “fuck tradition” sentiment.) So I was not going to have any cake at this gathering. Except that I could not stop thinking about it. I thought about it all day and all night. I dreamt about it. I tried to shame myself into rejecting the cake. Until I couldn’t any longer. So I got the cake. And my relationship with Korea and it’s traditions began to change. I started to understand what Natalia Ilyin calls radical traditionalism.

When I was pregnant with Eli, Ziddi, my husband, urged me to speak Korean to the baby when he was born so that he would be bilingual. I poo-pooed the idea. The baby was going to be American. Why would he need or want to speak Korean? (Self-hate goes deep and can manifest itself in many ways.)

I spoke of how I didn’t want to create an exclusive relationship with the baby where Ziddi would be closed off. Speaking American was going to be just fine. Except that when Eli was born, I could not BUT speak Korean to him. It was like a reflex I never knew I had: 웅야웅야, a comforting sound that translates to something like “there, there”; 옳지, that’s right; 우리 새깨가, our little baby, all came pouring out of me. My relationship with the Korean language re-booted itself in words of love, comfort and joy.

Race

As with gender issues, I would say that in my personal experiences, South Korea is a racist and xenophobic society. A part of our pride and national identity is in that we believe that we are a “pure blood nation.”

There is denial in the part of Korean people: we have had conflict with China and Japan for centuries, and everyone knows that raping of women comes with the territory of war and domination. And yet for the entire time I was growing up in Korea, “pure blood lineage” was a point of pride and honor.

The reality is that South Korea is becoming a nation with many mixed-race families and children. In our most recent history, a child of mixed race was pre-dominantly the outcome of the Korean War with American soldiers living in South Korea for the past 60 years. There were few visible children of mixed-race for most of South Korean history and their sorrows were hidden and tucked away. In the last two decades, South Korean farmers have seen a decline in women who are willing to stay in the countryside to marry into a farmer’s household. This imbalance was soon to be mitigated by the influx of women from Southeast Asia coming into a xenophobic society to become brides in the isolated countrysides to have and raise biracial children. The South Korean government was confronted with the unthinkable concept: having to teach Korean as a second language to grade school children. The reality of these children, who are Korean, but who are not easily accepted as such, is daunting. I think of the rage and humiliation of these young children and wonder how that will manifest itself in the next several decades.

Language

South Korea has a unique language and writing system. Hangul, a phonetic alphabet writing system, was developed by King Sejong in the 15th century. It was King Sejong’s idea that reading and writing should be a privilege that all of his country folks should have, not just the elite. Until this time, the only people who had access to literacy, in the form of Chinese letterforms, were the noble class.

Hangul consists of the 28 letters. The consonants were designed based on the shape of the mouth and the location of the tongue in relation to the teeth and inner anatomy of the mouth.

Here are some examples: ᄀ, ᄂ, ᄉ, ᄋ

Molar sounds: ᄀ, ᄏ, ᄁ

Tongue sounds: ᄂ, ᄃ, ᄐ, ᄄ

Lip sounds: ᄆ, ᄇ, ᄑ, ᄈ

Teeth sounds: ᄉ, ᄌ, ᄎ, ᄊ, ᄍ

Throat sounds: ᄋ, ᄒ

This design strategy reinforced the visual and physical learning relationship. The vowels were designed based on the concept of yin and yang, and the human being’s relationship to heaven and earth: Sky. The dot. Human. The verticle line. Earth. The horizontal line.This is where my research began.

About a year ago my friend posted an image on facebook describing the creative process (by toothpastefordinner.com.) You start the project with a long period of “Fuck Off.” Then you panic as you realize you don’t have a lot of time left. And then you do all the work while crying at the very, very end. How do I design? My process is the exact opposite of this. As soon as I started my project, I was crying and staying up late into the night obsessing over form and content. The following is what happened in the first few months.

I started designing a Korean typeface. Even though there are only 28 characters, due to how they combine to create syllables, when a type designer designs a Korean typeface, they must design, at the minimum, over 2000 letterform combinations. And that is just one weight. If you throw in an italic and bold, the numbers begin to multiply. This is a long term task, usually not fit for a one- person project. Not knowing anything about anything, I jumped in only to be faced with reality. There is a Korean saying: 하룻강아지 범 무서운줄 모른다. It speaks of the naivetee of the baby puppy not afraid of the tiger. That was me.

At that time, I was also looking at Korean words that are spelled and pronounced the same but have two different meanings. For example:

내,네,네:NAE (ae as in at,) NEH (eh as in met)

1.내My, 2.네Your, 3.네Yes.

I find it fascinating that in Korean, “my” and “your” are very hard to distinguish phonetically and that “your 네” and “yes 네” are spelled the same way. I asked my family members to phonetically spell out 내 and 네 into English. All of them (who are fluent in both English and Korean) started out with saying that “this is very difficult.” As if pulling teeth, they reluctantly wrote out the correct dictionary version of the pronunciation:

내 NAE (AE AS IN AT) 네 NEH (EH AS IN MET)

Personally, I don’t think it’s an accident that in Korean “my” and “your” is indiscernible. I think this has to do with boundaries. What is boundaries you ask? I did when I first heard the term in 1998 during one of my first therapy sessions. My therapist explained boundaries to me as something like this: not having boundaries is basically makingmy problem into your problem. My mind was a blank. I didn’t understand a word of what he was saying. “Isn’t that called life?” I thought. So then he gave me an example. A story about him and his wife. One day they were on vacation. They were in bed sleeping. His wife kept tossing and turning all through the night. Tossing and turning and sighing. Finally he asked his wife, “what’s wrong?” His wife answers, “I heard that a fierce thunder storm is coming and I can’t remember if we put a cover on the boat.” He went on to tell me that after that exchange his wife promptly feel asleep and it was he who started tossing and turning. He gave up at four am to get up, go out and cover up the boat. This was his example of “making my problem into yours.” I looked at him as if he were crazy. He did say that boundaries get crossed all the time between husband and wife and other intimate relationships. But the basic understanding was that many times it is inappropriate to make my problem into yours. For example, inKorea, sons go to jail on behalf of their fathers when the father commits a crime. Everyone knows that the father committed fraud, but the son gives a confession and goes to jail. This is seen as a noble deed. It is considered being loyal. A son that does not do this can be judged as having no loyalty. Boundaries. Boundaries had something to do with being able to say no. No to people who are important. Fathers. Mothers. Teachers. Students. Friends. When my therapist told me that having good boundaries and being able to say no was the way to a healthy life, I thought this sounded like a cult. The cult of BOUNDARIES. Surely, no one can desire to be so happy as to say no to people who have claim to you? I asked my sister-in-law who was a Ph. D. student in psychology about the concept of boundaries. I asked her, what is this word inKorean? And of coures. She said we didn’t have one. And as much of an impossibility as it seemed, it also seemed like I had boundaries.

When I was married to my first husband, a Korean man, my then mother-in-law tried to make it my job to make sure that my husband give up fatty foods, something she says she struggled her whole life trying to teach him. I looked at her and said, “if you didn’t succeed for thirty years, how do you think I will? I think this is his lesson to learn for himself.” Unknown to me I had boundaries. I was called out for it all the time. It was called as “being rude, obstinate, arragent, smart-ass and yes, bitchy.” But it turns out, I’m a natural.

I exercise my boundaries as a teacher when I try not let my personal preferences get in the way of my students learning. Because sometimes, it’s not about me. And I can’t make my problem into your problem. I exercise my boundaries as a parent when I try not to let my prejudice get in the way of my child’s exploration of the world. Because sometimes, it’s not about me. I exercise my boundaries as a partner when I try not to let past pains get in the way of understanding new joys. Because sometimes, it’s about us.

Boundaries will get crossed. All the time. Our administrative assistant at school has a sign that reads: “your lack of preparation does not constitute an emergency on my part.” This is very true and it adhere’s to the rules of boundaries. But in life there is always room for compassion, which is another concept all together from having boundaries. But if this were a lesson in graphic design, I would encourage people to learn the grid system, before they try and go break it.

The important thing about boundaries is: are you aware of what is going on, and are you contributing to an inappropriate relationships? Let’s look at the metaphor of giving hungry people fish versus teaching them how to fish. Giving a hungry person a fish does not necessarily empower them. They will come back to you for more fish, for it is you who hold the power of having the fish. Teaching them how to fish will allow them to survive on their own. They will not need you anymore, but that is a good thing. I feel exactly the same way about teaching. I look at teaching as giving tools for thinking, making, and processing self-knowledge. This is how I understand boundaries.

A Good Crit Is Needed At Times, But Really, Is This Where I Want To Start?

How I feel about Korea is that I start with complaints and judgements. My Korean language of self-talk is rooted in harsh criticism and negativity. The glass is not half empty: the glass is going to break, and then I have to dig a hole in the earth to look for water that is not actually water but mud.

I worry that I need to be more positive. I worry that my complaints will be understood as “I don’t like Korea.” I worry that if I give voice to my complaints, I will be rejected again.

For now, I give myself permission to create these studies without judgement, as an exercise in giving voice to what I am seeing and experiencing.

Judgmental Broadsides

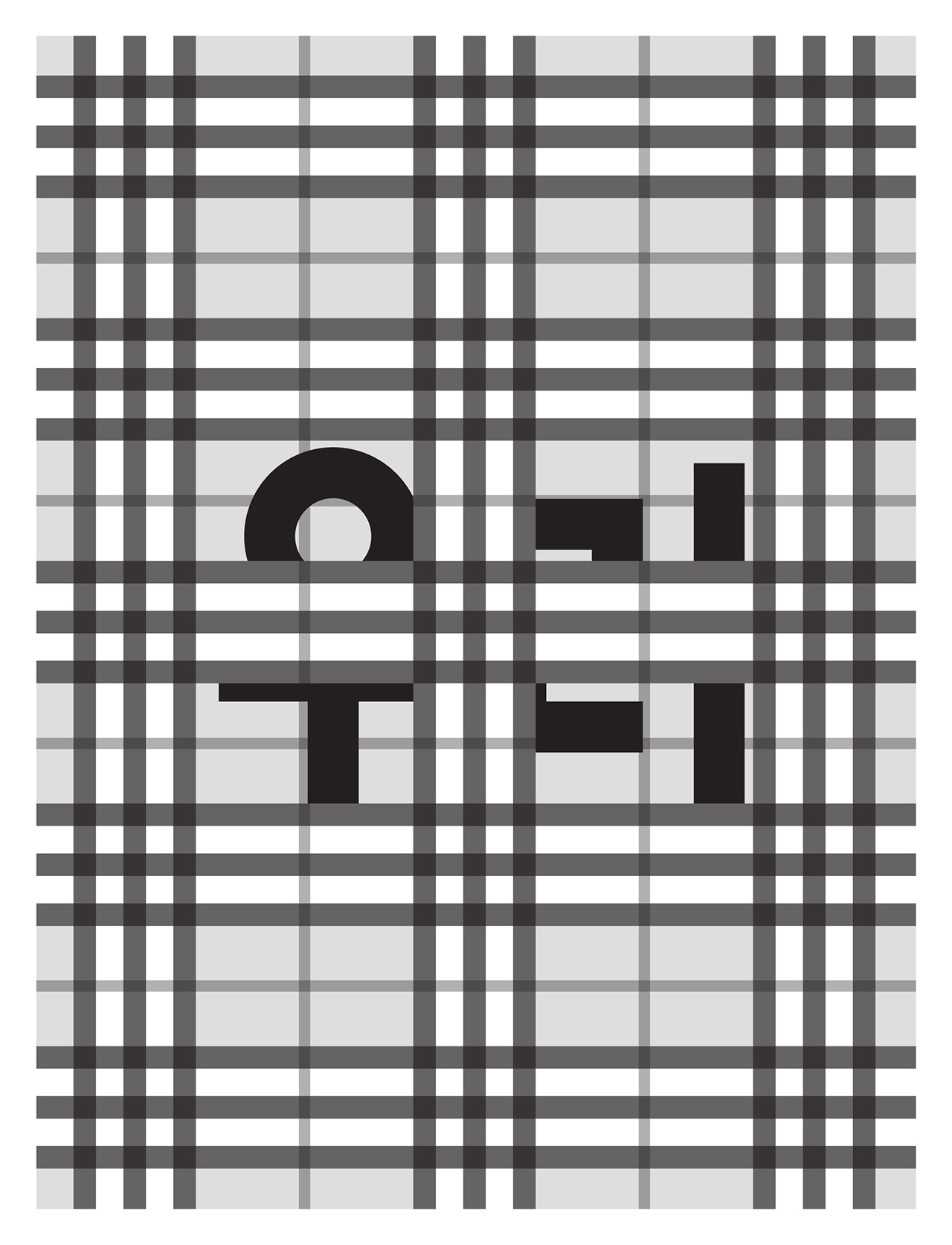

When I go to Seoul, I see labels. Labels of class, labels of gender, labels of education, labels of consumption. So my first visual study starts with labels, and especially luxury brand labels. I focused on two brands: Burberry and Louis Vuitton. I recall these two pattern textures as iconic luxury brands when I was growing up in Seoul. I juxtaposed the list of Korean words that have double meanings to these brand patterns. The first word I started with is 빔.

빔: BEEM

Meaning: 1. Dressing in new clothes for the holidays. Or meaning “new clothes.” Meaning: 2. Empty. Nothing there. The two different ironic meanings were just the right place to start. It helps that this word is a bit obscure and does not find their way into everyday language.

내, 네, 네: NAE, NEH, NEH

Meaning: 1. My, Meaning: 2. Your, Meaning: 3. Yes

우리: WOO-RI

Meaning: 1. Us, Meaning: 2. Pen (as in for animals)

궁: GOONG

Meaning: 1. Palace (for kings and queens), Meaning: 2. The state of being poor

공: GONG

Meaning: 1. Merit Meaning: 2. Emptiness

자비: JA-BI/BI-JA

Meaning of Ja-bi: 1. Mercy, Meaning of Bi-ja: 1. VISA as in credit card, or 2. visa as in paperwork required to enter a country.

The tension between these conflicting words is how I feel about Korea. With confusion and curiosity, I continue my visual explorations of these concepts. I started looking into ways of sharing the little collecting that was starting to gather. The first impulse was to make it into a book.

I also sent off some design ideas to spoonflower.com to make these designs into fabric. And while I waited, ideas started to flow. I started thinking about draping and making clothes out of this fabric. And as a short cut to a visual idea, I made a quick contour drawing of myself and started mixing and matching clothing items to the pattern studies that created a certain narrative.

The title, “I am not the sum of my parts” evolved around this time. So where do I go from here.

The Project: GENDER AND RACE IN SOUTH KOREA: A STORY TELLING PROJECT

In 2013, the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison came out with a report titled “A Few Observations on Publishing in 2012”. The authors of this paper (Kathleen T. Horning, Merri V. Lindgren, and Megan Schliesman) write, and I quote: “The CCBC receives most of the new trade books published each year by large trade publishers in the United States, and many by a number of smaller publishers. As we have done for the past twenty-eight years, we continue to document the number of children’s books we receive annually by and about people of color. The news in terms of sheer numbers continues to be discouraging: the total number of books about people of color—regardless of quality, regardless of accuracy or authenticity—was less than eight percent of the total number of titles we received.” End quote. Less than eight percent. This data is not from the 1960s. It is from 2012. And even if we double the numbers to account for all the possible mistakes and errors, we have the number of 16 percent.

Having experienced a homogeneous culture as an outsider, I know the power of seeing a book or a movie in main stream media, where a symbolic figure of your marked body is represented within the confines of the dominant race and class.

Right now, I’m looking at creating picture books with the multi-racial children of South Korea as well as the United States as the primary audience. I want to create an experience for these children that they are acknowledged by main steam media in the form of a published book.

I am in the process of writing short stories about the simple lives of children regarding everyday things such as the first rain storm or the first lost tooth. This story book will not be about legacy burdens, but it will be a book of everyday experiences.

This book will be embodied by people of mixed-backgrounds, multiple races and thus finding that they are, even in a very small way, visually represented as part of their community and country. This study is about hope and the willingness to be hopeful about the future. This study is about small seeds that get planted, not knowing if it will take root. This study is about running away from home, only to realize that it is not too different from where you currently choose to live. It’s never about them. It’s about us.Mysneakers | Nike