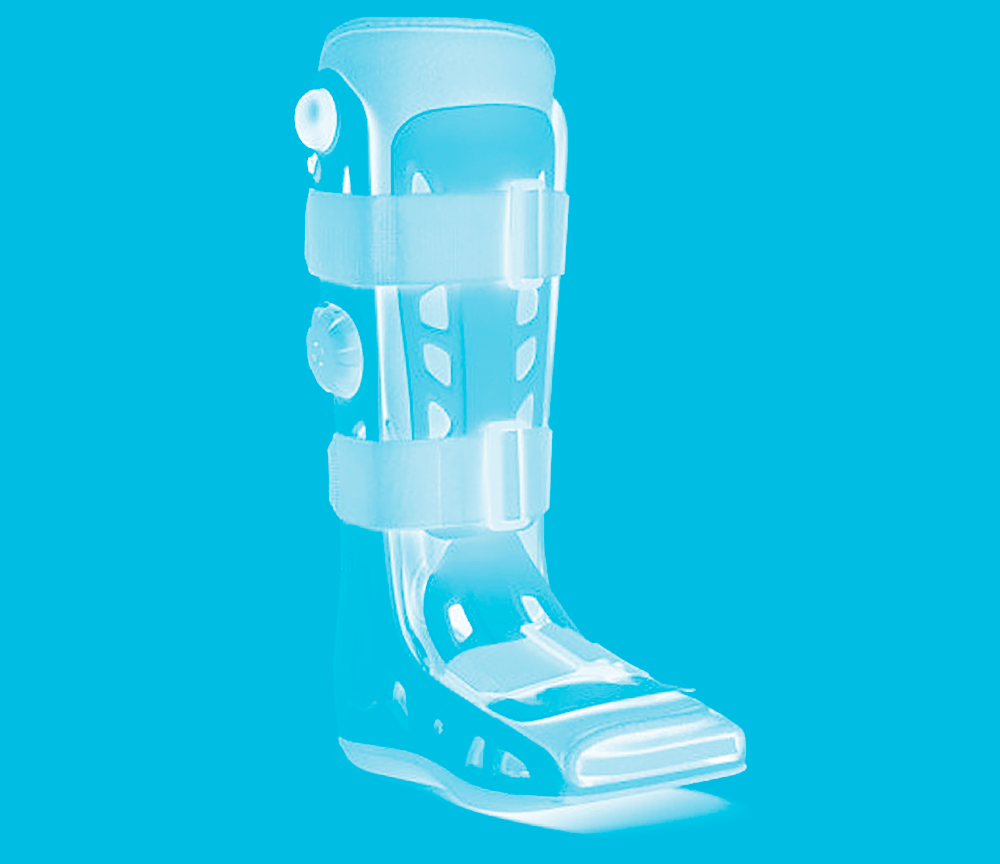

On the day after the Senior critiques finished up last month, a student hobbled into my office for her post mortem, wearing sweats and a tendonitis boot. This student, along with making work for her first Senior Degree Project critique, had overworked her body, preparing to dance the Snow Queen in a local company’s annual Nutcracker ballet. And so, the boot.

Some dancers are not highly intellectual, being creatures of movement, but the Snow Queen is not that kind of dancer. She is bright, verbal and as interested in philosophy as she is in design. Planning to end her career as a performer at the end of this season—20 is getting up there for a dancer– she had over-trained in a quest for perfection, and her ligaments hurt. When she came to my office, she was tired, battling pain, and, in her polite way, angry.

That first Senior Degree Project critique is never easy. The groups of critics don’t know each other. The time allotted is always too short. The critics are a good mix for one student and nonsensical for another. The student must explain the beginning stages of a year-long project to strangers who know only what she has written about her goals for the project. The critics feel as though they must give the school its money’s worth, and so tend to “throw fish”– give top-of-the-head solutions—or point out seeming deficiencies in form, form that the student has not yet begun to think through. When I was a critic, I did all these things.

It is ever thus, and has been at every institution at which I have ever taught. We work to make critique better each time, but each time responds to different curricular changes, different departmental emphases, different provostial dicta. And so the days after that first Senior crit are hard, because the students have been knocked around, even at the most student-centered, kindly institution. The rubber has met the road. Rough hands have searched the pudding for its proof.

But back to the Snow Queen. She clomped in and sat down gingerly. We talked about the crit. It had been wide of the mark. It hadn’t helped her. And then she said something that echoed comments I had been getting from other students, but had not yet really heard. She said, “Why isn’t beauty enough? Why can’t I just make beautiful things? Why is everything I make not “edgy” enough, not “socially aware” enough, not “corporate” enough?”

A saturated solution, liquid in the test tube, will crystallize suddenly if you give the side of the tube a good flick with your fingernail. The Snow Queen’s comment jarred me: and saturated thoughts crystalized.

When we teach design, we take people who are talented at making things and put them through a process of inculcation in how to make work that will succeed in the marketplace. That marketplace might be an NGO, a zine commune, or a UX manufactory, but we teach our students how to make work that will make money for someone. We take people who like to doodle, and we teach them how to doodle in an edgy way, in a stylish way, in a way that will convince people of that doodle’s up-to-the-minute hipsterness, and that such hipsterness deserves the spending of their dollars so they can own a piece of it. Design is integrally associated with selling things, and to pretend it isn’t is to live in la-la land.

When we teach design, we take these makers and these doodlers, and involve them in complicated codes about art and design and their places in the world. (“But designers are not artists!” you say, bowing to the contemporary notion that all people belong in boxes.) Forgive me if I expect you to be both artist and designer. Art is representation. Design is representation. Art is bought and sold. Design is bought and sold. Perhaps the truest artist is the artist who does not compete in the marketplace, never sells her work. We call that person an Outside Artist, and mark up the price when she’s dead. But every other artist,making work to sell, is really a designer, because—even when not fully conscious of it– she responds to the whims of the society, of the buyer, of the marketplace.

The Snow Queen’s question comes down to the role of beauty in art and design. Is there room for beauty? Any discussion of “beauty” seems terribly out of step, so 19th Century. Our ears are accustomed to the rapid gunfire of shocks and upsets that is our current experience of techno-drenched culture. Anything else seems unreal, seems inaccurate–seems wrong. The Futurists believed that war was the ultimate artistic gratification of a sense of perception that has been changed by technology. They valued war instead of beauty. And we follow suit like good little children. Why have we decided that we must throw ourselves into living out Marinetti’s vision? Walter Benjamin once said that championing this Futurist “realization” was the ultimate expression of the notion of “Art for Art’s Sake.” And he thought it profoundly stupid.

Why do we feel that we must use our minds and talent to magnify disruption, horror, and violence in the name of “realism?” We collude to create a phantasmagoric internet mash-up that is far larger, immediate and far-reaching than the actual horrors going on right now on Earth.

In my experience, some people—some students—come to school “trailing clouds of glory.” They have somehow, through living, perhaps, picked up the notion that it would be fulfilling to make beautiful things. Things that please the eye. Things that go together. Things that make wholeness, that make happiness, that are aesthetically enjoyable. We spend four years trying to pound this desire to make beauty out of them. Our own schooling—a schooling in the postmodern– gets in the way of our allowing such a search to continue. We try to break it up. Make them see the light. Open their eyes. Break the pattern. Push the boundary. For beauty to us is not “true.” Truth, as we all know, is ugly. Truth is the fighting in Syria. Truth is the corporate reorg. We want our students to have their eyes wide open, nimbly encountering the incoming missiles of contemporary culture with alacrity and fortitude. That is what we think teaching design is about. We are wrong.

We are wrong when we teach people to abandon a search for beauty in favor of a trendy edginess, in favor of do-gooder trumpeting, in favor of the stale avant-garde bursting of the bourgeois balloon. Bursting balloons was all very well in its day. But today, all balloons have been burst. Our world is not in need of more breaking apart, but of more putting together. The challenge these days is not one of pushing against the hard and fast rules of a striated culture– opening up and revealing– but of of finding ways to create enclosure, resolution and unity. Beauty depends on harmony, harmony depends on relationship. Design, at its finest, makes relationship. Why are we still invested in trying to teach our students–as another student has said– to break things instead of make things?

The Snow Queen hobbles in retreat, the clack of her boot echoes in the hall. In our time, the value of beauty–perfect or imperfect– has suffered grave injury. In trying to play by the rules and avoid anything smacking of sentiment, of emotion, (those hallmarks of Marinetti’s much-detested “feminine,”) we’ve allowed the modernist agenda, and its partner postmodern irony, to wipe out much of what can be considered the best in humankind. We do not have to continue doing so.

The avant-garde is tired. Postmodernism is long over. Students do not need to be schooled in the edgy, socially aware, or corporate. They are more edgy and socially aware than their teachers can ever be. Corporate whomps on the head come with experience, we don’t need to approximate them. If students want to learn craft in order to make beautiful things according to their own lights, can we help them make beauty? Can we nurture that instinct, rather than destroy it?jordan Sneakers | Women’s Nike Air Jordan 1 trainers – Latest Releases , Ietp