VCFA MFA in Graphic Design Co-chair Ian Lynam sat down with Matt Monk, Dean of VCFA and founding faculty member in the Graphic Design Program to talk about how one goes about starting an MFA Program, what’s at stake, and what the takeaways are.

Poster design for an exhibition of contemporary music posters at Vermont College of Fine Arts, 2012. Designed in collaboration with Nikki Juen.

How did you first get involved in building the the MFA program in Graphic Design at VCFA?

In December of 2010, I was minding my own business as a professor of graphic design at Rhode Island School of Design. I got home from class one evening to find an email from Tom Greene, the president of VCFA. He told me that VCFA was starting a graphic design program and he wondered if I would be interested in talking with him about being founding faculty chair. At this point I had never heard of VCFA, and I was perfectly comfortable in my tenured position at RISD, so I politely declined. Anyone who has met Tom Greene knows that Tom is persistent and he loves a challenge. We then talked by phone and next thing I knew I was driving to Montpelier to meet Tom and his staff, to see the campus, and to hear more. I was genuinely impressed with what I saw and heard. In that short trip Tom offered me the position of founding faculty chair.

I have to say that when I was offered the position, I imagined that this would likely be the only opportunity I would ever have to start a new design program from scratch. In addition, because of the outstanding reputation of the long-established programs at VCFA (MFA in Writing, MFA in Writing for Children & Young Adults, and MFA in Visual Art) I could see that VCFA was an institution that valued, and even expected, its programs to operate with strong academic integrity and a high level of autonomy. From the start, I have known that the administration at VCFA lets programs make academic decisions that are appropriate to be made at the program level, while they actively support programs in any way they can. From my first meetings with Tom and Gary Moore (the academic dean at the time) as well as the administrators of the existing programs, I could tell that the College not only talked about operating in this very supportive way, but that they actually knew what it meant to practice this approach and had applied it successfully in their other programs.

I was tremendously interested in the unique pedagogical model–the student-centered approach. The evolution of my own teaching had been leading me toward student-centered learning, even before I knew the term. I had not been aware that student-centered learning was an established model, one that John Dewey and others involved in progressive education had outlined over a century before. Once I found out a little bit about this approach through my conversations with the folks at VCFA, and through subsequent research inspired by those conversations, I knew I had found a place that felt right to me.

My own experience in graphic design education–as an undergrad, a graduate student, and a teacher with many years in the classroom–had been mostly based on what I now see as a top down approach–a model in which the teacher is seen as the authority, and the pupil is seen as an empty vessel into which academic content is poured. I think that much of education in general uses this model, and I believe that graphic design education has suffered even more, in part because much of the way graphic design has been taught has been to deliver a white European modernist aesthetic and approach, handed down by mostly white men in a paternalistic fashion. I saw the chance to develop a program at VCFA as a unique opportunity to develop a program that could get far beyond these conventions of teaching design. So I signed on as founding faculty chair.

Another part of my decision was based on the unique administrative structure of the VCFA programs. In my mind the structure is quite sensible and successful. The leadership of the program is shared by a faculty chair or co-chairs (the academic leader of the program) and a program director (the administrative leader of the program.) VCFA has a history of hiring brilliant administrators who are good at their jobs. It was refreshing to know that I would not be responsible for the administration of the program, and that this would be taken care of by someone who wanted to do this job and did it well. The program was very lucky that Jennifer Renko was hired as the founding program director. Jenn has been a very big part in the building of the program and in the successes that the program has achieved.

Design for the cover of a book on the work of architectural glass artist James Carpenter, for Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 2012.

How did you guys go about assembling the initial faculty?

I went back to my room at the inn in Montpelier on the evening after I met with Tom and the others on campus, and I made a list of all the people I knew who I would want to hire as faculty. The list comprised people who I respect and know well, people I knew would be able to work together to build a great program. As you may have heard, over and above all other important professional qualifications, I had one primary rule: no assholes. I’ve seen asshole faculty members ruin the vibe of a program. I’ve seen divisive faculty, and people who want to reject any idea that isn’t their own. I’ve seen cult-of-personality types who make it all about themselves. I’ve seen people who hold grudges for decades. If this program was going to have any of those, then to me there was no point in doing it. This program was about eliminating that negative dynamic from the faculty. I worry that this could sound like I just hired all my friends. As it turns out, many of them are dear friends. But I like to think that they are friends because our friendship is based on respect and shared values. And then when I had a chance to invite them to join me, I did it not invite them because they are friends, but because of the respect and shared values that also, as it happens, made me want to have them as friends.

When I made my list, and it became time to hire them as faculty, I supplied bios and CVs of each of them to the president and dean and senior staff, who approved them all wholeheartedly. We hired them, and they are all on faculty today. It’s my dream team. I know that’s a corny phrase, but it’s true. And I can honestly say that as the faculty team has grown, it has gotten even better, because original faculty members have brought in their trusted colleagues. I am so proud of the group we have assembled and of how the group functions as a collection of individuals and as a unified whole.

What were your goals in starting the program?

My initial goals were these: to start a new program in graphic design that would build on my positive experiences in teaching, allow me to assemble a remarkable group of faculty colleagues who comprise an amazingly diverse group of like-minded educators, and create a program that could reach a wide range of potential students, including many to whom conventional MFA programs were unavailable.

One of my first goals was to establish a sense of community and a productive tone for the program–a tone that is truly conducive to teaching and learning. I worked hard to identify faculty members who would fully embrace VCFA’s unique pedagogical model, and to find people who I knew were capable of working as part of a genuine collective. The program has assembled a group of faculty who are actively engaged in both teaching and design practice, who–refreshingly–genuinely embrace change and new ideas, who are involved in teaching for the sake of educating whole students, and great thinkers who seek to expand their own practices through the process of academic exchange. As a result, not only do we have highly visible faculty members who are talented designers and accomplished educators, we have a faculty that works unbelievably well as a group. It’s a group that sees itself not as a collection of individual teachers, but a collective body with common goals. We talk ideas through, no matter how difficult, in ways that I have never seen in academia. This collective attitude has fostered a similar spirit that permeates the culture of the program. Our faculty members value the sense of community they feel not only with their teaching colleagues, but with the entire program. As the program has grown, and faculty members have been added, we’ve been both extremely careful, and extremely lucky, to have identified new faculty who bring unique skills and experiences, enhanced diversity of all kinds, and who have blended beautifully with the group. This sense of community has been very important, not only to me, but to everyone involved in the program.

Poster design for the Foundation Studies Triennial Exhibition at Rhode Island School of Design, 2011.

You are both a faculty member in the program, as well as the Dean of VCFA—how do those roles play out?

I accepted the position of dean because I have always felt a need to continue to evolve and to push myself to take on new challenges. While taking on the job of dean seemed a somewhat obvious next step for me as an educator, I’ll admit that it scared me a little. And yet, I believe that we should be pushing ourselves beyond our perceived limits continuously. Stasis is the enemy of art, design, and education. Obviously, I had a hunch that I could succeed in this position, and that I had the necessary skills. But my hunches were untested. It can be incredibly empowering to take on tasks that are a little scary. I have learned a great deal and feel that I have made some positive contributions while I’ve been here. It is difficult work at times, but it is satisfying to be learning so much and seeing evidence of progress.

And yet, I have always loved teaching. While most of my duties as a dean are administrative, I still consider myself primarily an educator. So for me, teaching is incredibly important. In the same way that maintaining a design practice keeps a teacher connected to the discipline, for me, keeping a hand in teaching keeps me connected to education as an administrator. I can’t imagine giving that up. As you might guess, I also feel an unbelievable connection to this remarkable program and the faculty and students in it, and feel a very strong desire to remain involved. Part of what makes this program so successful and so rewarding for everyone involved is that we all feel such a powerful personal connection to each other. More than I have ever seen in any design program.

This is definitely a result of common goals that we as a faculty, staff, and student body all share. I wrote about it in the essay “Tasers of Kindness” published here recently—we consciously try to minimize (and dare I say, potentially reverse!) “pedagogical damage” and to ensure that the visiting critics/designers we invite are proactive and prosocial in their time here.

Have you always approached teaching design from this perspective?

I’d like to say that I have. But that wouldn’t be entirely true. For me, I think it is something that emerged over time as I have been teaching. When I began teaching, like many designers who are starting out as teachers, I had no formal education or training in teaching. All I had was my familiarity with the subject matter, and my personal thoughts about teaching, which I realize now were little more than a collection of assumptions and biases about teaching and learning. After gaining years of experience, talking regularly with teaching colleagues, and basically taking an extremely self-reflective approach to teaching, I’ve developed a practice in education that feels right for me and seems to be effective and satisfactory for students.

After I had been teaching at RISD for about 16 years, I enrolled in a collegiate teaching course at Brown University that was fantastic. I was in the course with many Brown graduate students who had never taught. So their education about teaching was almost purely theoretical. I had the benefit of being able to consider the theory in relation to not only my past teaching, but the teaching I was actively doing at the time. I learned a great deal from the program, and was happy to have theory and terminology to apply directly to actual experiences.

Around this time, I was experimenting in the classroom (it sounds sort of irresponsible when I phrase it that way. But when you get right down to it, I think a classroom always is, or always should be, a laboratory for experimentation) with ideas about what I now have the language to call student-centered pedagogy, and inquiry-based learning. I was looking for ways to get students to take a more active role in their own education, and to challenge the idea that the faculty member is the person with the knowledge and answers that the students are seeking to uncover. I prefer to see the student as the expert in the topic he or she is exploring, and the faculty member is an insightful advisor who can help guide students to make discoveries for themselves. Of course, this approach really blossoms at VCFA. That’s basically what we do.

How would you describe your personal practice?

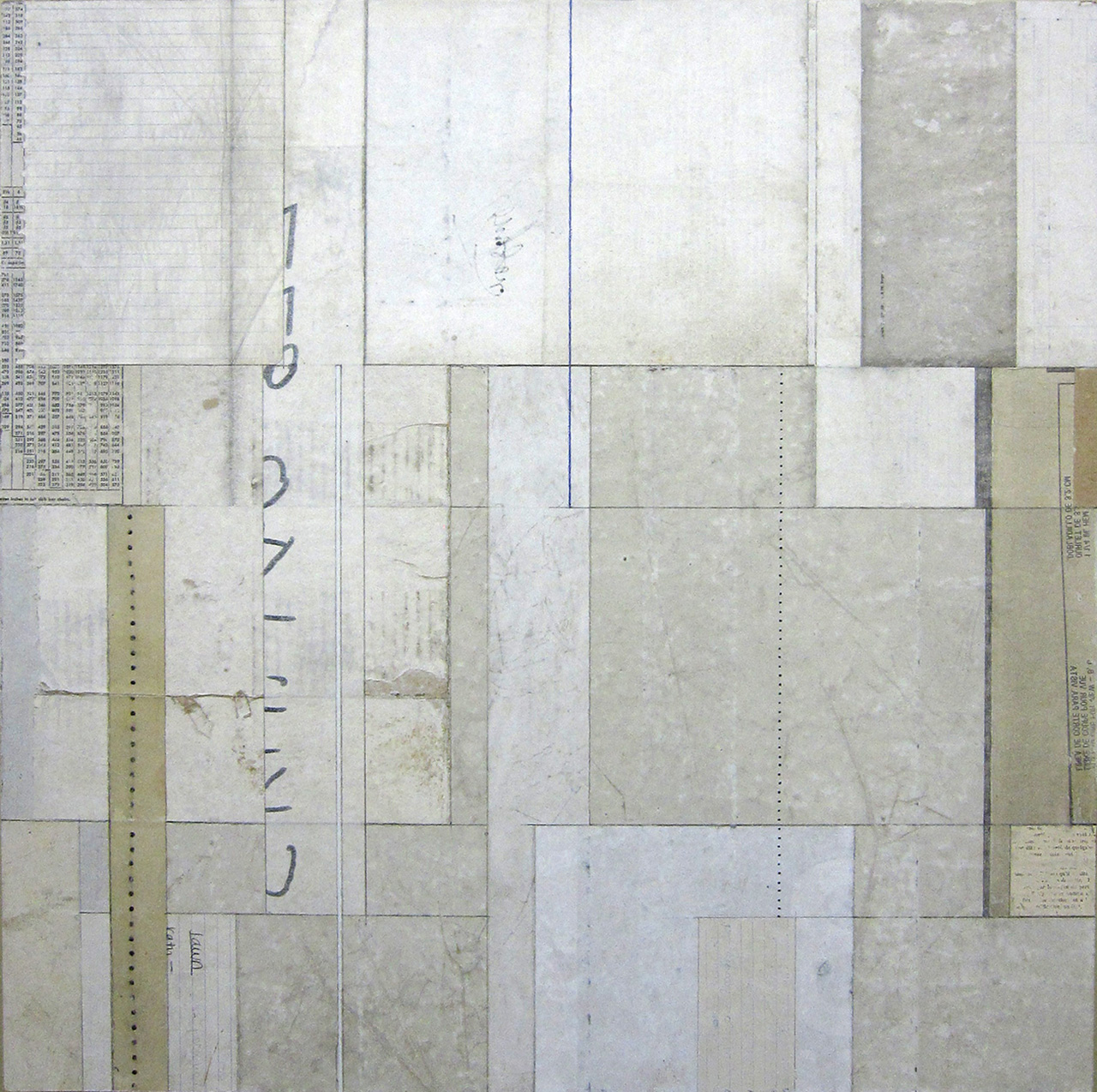

My personal practice is somewhat complicated these days. For one thing, being a full time administrator and a part time faculty member means that I don’t have nearly as much time for my personal practice as I would like. But I do maintain a practice, and I find it incredibly important. I have always been one of these makers who feels equally at home in both art and design, and yet not entirely at home in either. While I was working on my MFA in graphic design, I became obsessed with a way of working that felt just right for me. A very personal style that explored imperfection, accident, chaos theory, taoist philosophy. This was in the very early stages of the computer as the dominant tool for design, which I rejected, to a degree, mostly on aesthetics–including not only the aesthetics of the end result, but the aesthetics of making. Until grad school, my practice had been almost entirely off the computer (or really pre-computer) and I had fallen in love with the physical ways we made design back then: cutting, gluing, painting, photographing, doing paste-up and making design comps. I signed on for design in large part because of my love of making tactile objects with my hands. In grad school, I discovered many satisfying ways to take this physical work further, but I realized that there was little room for this way of working in any commercial graphic design setting. After grad school, I worked in some respected boutique design firms, and developed a practice designing books primarily for art and architecture. That has been an ongoing and rewarding design practice that has been executed almost entirely on the computer. And yet, my practice on the computer has never left me fully satisfied. I have continued to make work by hand. This has mostly been work that probably falls into the category of art, as opposed to design, and yet most of this work is very much about design, especially the physical making of design before the computer. To me, much of my art relates to paste-up and comping. Much of it includes typography and nearly all of it includes orthogonal grids, often drawn with T-squares and drafting tools, that evoke my swiss-derived graphic design education. And yet, I think the work functions more as art than as design because I tend to work at a certain scale and to make pieces that ultimately seem to belong on a wall. In addition, I find that the way others interact with them is more like people tend to interact with paintings than with conventional works of design.

I have never felt like there is much point in clearly defining differences between design and art. And even if we could define differences, I certainly do not believe that there is any hierarchical difference between art and design–that one is “above” the other. I remember you, Ian, once saying pretty vocally at a residency that you believe that art is a subset of design. I completely agree and I have always felt this way. But still, I continue to have unresolved feelings about the differences between the two. I believe that in many ways our culture has always elevated art above design. And I think that’s unfortunate. And yet, in some ways it seems to free designers up to work a little more quietly and under the radar, to make surprising work, and work that is unexpected and powerful. Contemporary culture seems to expect less of graphic design, which means it can be that much more successful when it really works. Of course design has come a long way in recent years and decades, in terms of respect as a discipline. But I think we still have a long way to go.

That is an interesting point–I think that in contemporary culture, design is thought of as being goal/outcome-oriented, whereas the practice of fine art is given much more hazy affordances in terms of end products/results. What do you try to bring to teaching that expands these boundaries–either in terms of expressing your own personal philosophy or questioning student expectations?

For me, the essence of both art and design comes down to the complex relationships between form, ideas, and context. If we’re talking about a work of art or design, we could talk about what it looks like (its form), what it means (its ideas), and how it functions in the world (its context). I’m interested in each of these three elements, and more importantly in how these three elements affect each other. On one hand this sounds pretty simple, but it’s actually a basis for exploring very complex relationships. So, whether it’s my own work of art or design, or the work of a student, I tend to think in these terms.

What are some of the most exciting things about the Graphic Design residencies for you?

This question is almost impossible to answer, because everything about this program is exciting to me. But If I stick to your question, the first thing that comes to mind is this: I live in Montpelier year round. Most days, we have no programs in residence. So I am working away with many other talented staff members, on programs that are literally invisible to us most of the time. All residencies on campus make the programs suddenly and completely visible. We are reminded why we do what we do to support these programs. With the graphic design residencies, I have not only the suddenly visible effect, but I feel like my people are here with me.

Each residency is like the Christmas mornings of my childhood with all of the anticipation that leads up to it. I honestly can’t wait to see the faculty and students, to see the work that they have been making, and to dig deep into discussing the work.

And most of all, at each residency, I am reminded–confronted with evidence really–that this wild educational experiment we have put in motion is actually working–and working really well. I could never have imagined that in such a short time, we would have faculty and students who have accomplished so much, learned so much and, felt so rewarded by the process, and built such a powerful community.Buy Sneakers | Women's Nike Air Max 270 trainers – Latest Releases