Sibylle Hagmann started her career in Switzerland after earning a BFA from the Basel School of Design in 1989. She explored her passion for type design and typography while completing her MFA at the California Institute of the Arts. Over the years she developed award-winning typeface families such as Cholla and Odile. Cholla was originally commissioned by Art Center College of Design in 1999 and released by the type foundry Emigre in the same year. The typeface family Odile, published in 2006, was awarded the Swiss Federal Design Award. Her work has been featured in numerous publications and recognized by the Type Directors Club of New York and Japan, among many others. Sibylle Hagmann is a Professor of Graphic Design at the University of Houston School of Art.

VCFA’s Ian Lynam sits down with Sibylle to chat about design, education, type and criticism.

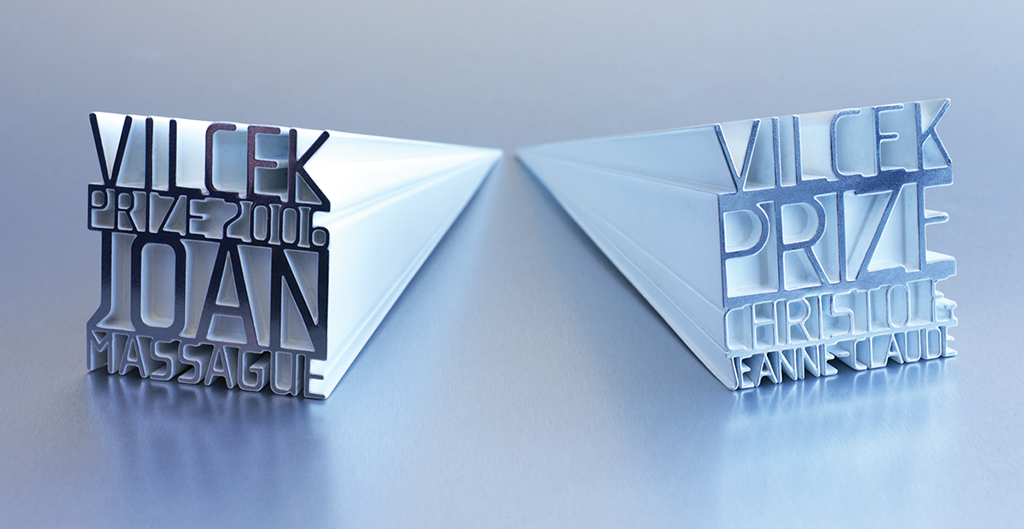

Sibylle Hagmann’s typeface Cholla in use: The Vilcek Prize award trophy was created for a major new award program honoring outstanding achievements of foreign-born Americans within the fields of the visual arts and biomedical research. Trophy designed by Sagmeister & Walsh.

You are both a type designer and a design educator—how is it that you balance both sides of your practice?

The two activities are somewhat at opposite ends of the professional spectrum, yet there’s a sufficient duality within these sets of expertise. I think I find most balance by going back-and-forth between type design and design education while trying to bring in some in-between-time. Teaching can be thoroughly intense and I often need a quiet day to recuperate and digest the many discussions that I still have floating in my head. Days at school also transport me into a lively environment that is simultaneously stimulating and gregarious. Whereas type design—at least how I practice it—can be a pretty lonely, lab-like activity. It’s an introvert pursuit that consists of meditatively and minutely nudging details. Developing type takes time and more often than not, specimens need to be stored away to gain some distance and objectivity, so while I sometimes wish there was much more time for type, the reciprocity has its own value and benefits.

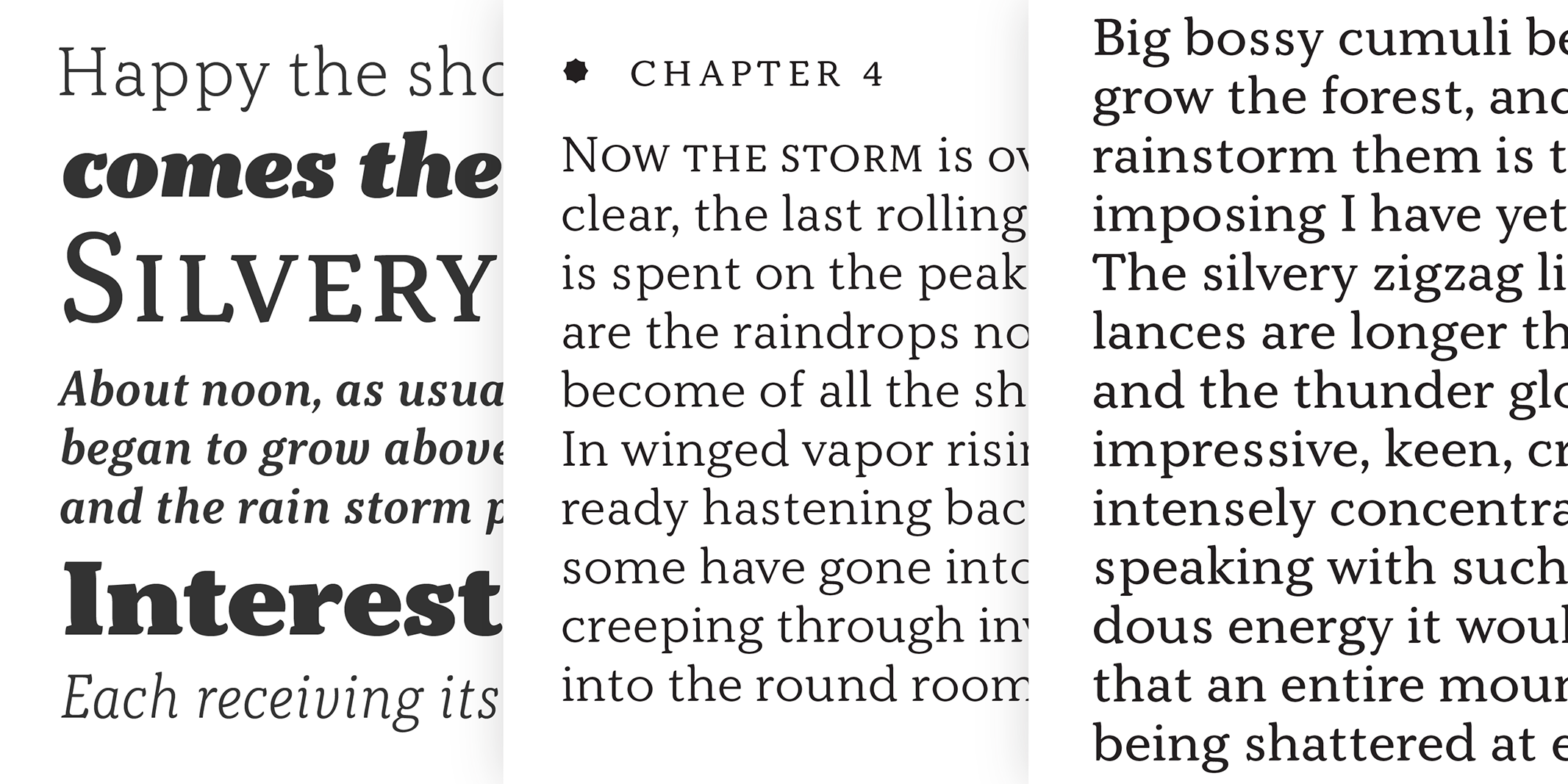

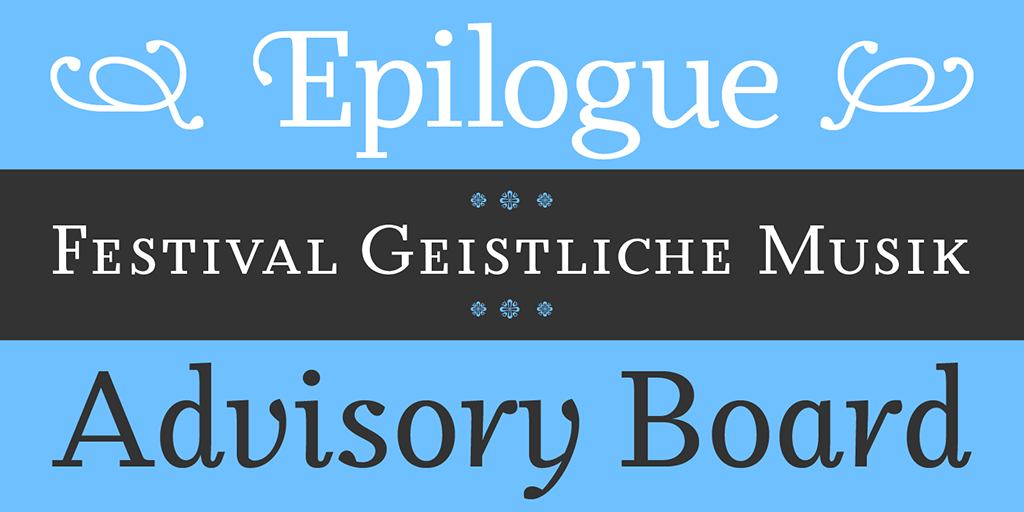

Sibylle Hagmann’s beautiful new typeface family Kopius, released by her type foundry Kontour.

Sibylle Hagmann’s beautiful new typeface family Kopius, released by her type foundry Kontour.

What are aspects of your studio practice that you bring into the classroom and vice-versa?

The craft of type design involves developing a system of forms defined by the standards of an agreed-upon written language. The absolute final end product, how a typeface is being used, in what context and kind of content affiliation remain an unknown, yet commercial type is in its own right user- and application-oriented.

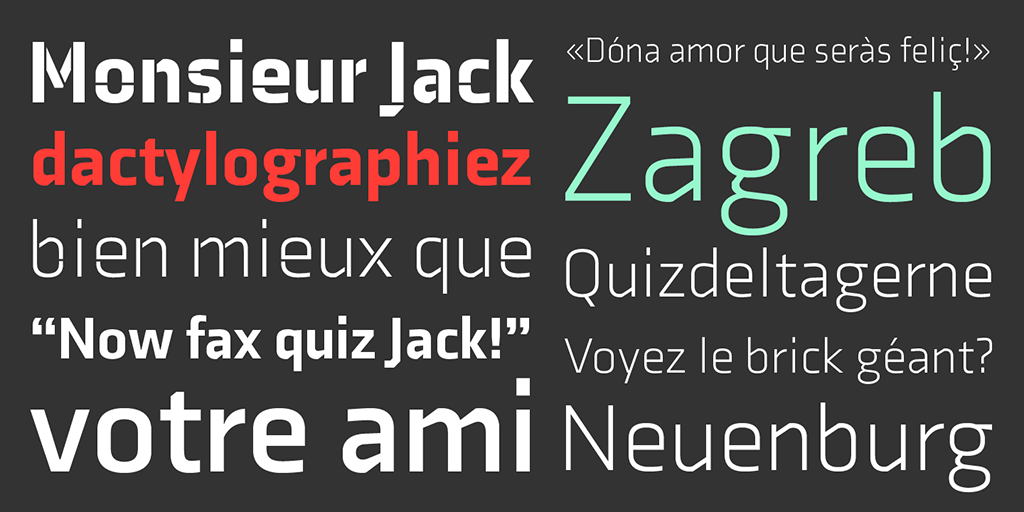

Sibylle Hagmann’s recent typeface family Axia, also from Kontour.

In practice, I’m working almost exclusively independent of clients, so in most cases the user remains unidentified. This allows for a certain creative freedom that circumvents a preconceived visual notion of a predefined end-product and application. With type design projects I’m speculating on a possible use and demand without marketability research. Obviously this approach entails the risk that my typefaces end up as mostly just speculative contemporary form.

Sibylle Hagmann’s elegant Odile family of typefaces.

Similar to my practice, for most teaching assignments the client is anonymous, allowing the student to freely define an audience and maintain creative freedom, the core of many assignments are situated around tentative problems that allow for experimentation and interpretation. I also see a parallel in how graphic design education stimulates research and making, processes that focus on producing cohesive and effective narratives and a successful visual information system, not unlike the conceiving of a method that makes up a typeface family.

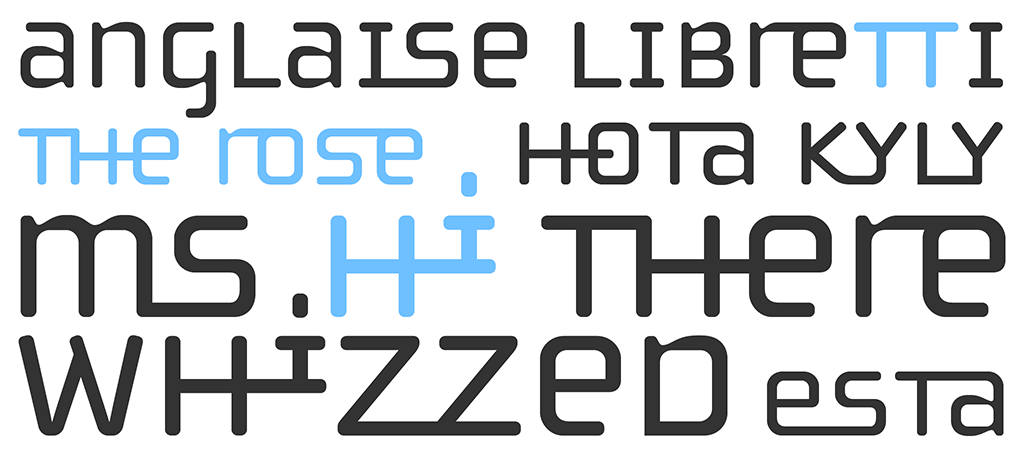

Sibylle Hagmann’s rugged Elido family of typefaces.

Over the years, type design activities and research have in turn also prompted a deeper understanding of typography and typographic history, which I happily bring back into the classroom. And, as a small independent foundry needing some promotion I’m busy with a range of studio tasks and activities—practical experiences—although transformed in some ways I pass on into the classroom. Conversely, dialogues happening in the classroom “flow” back into my practice. I’m constantly learning from students and I’m often fueled and thoroughly impressed by their hard work and dedication.

Sibylle Hagmann’s futuristic Cholla family of typefaces.

Finally, the practical side of teaching is that I have to keep abreast with the design profession, tools, and movements.

In the contemporary North American landscape of design education, design departments tend to be either portfolio-oriented or process-oriented. I find it interesting that for both your commercial ‘clients’ and for your teaching projects, the audience/client is ambiguous and unknown. Does that help add to the mystique of situations in the classroom or for your foundry?

Design education has to be process oriented. A portfolio-oriented program does not produce designers with a vision, but prepare workers for production. Design is about finding the right solution from boundless and infinite possibilities. The design process is defined by developing a method, learning from personal research, failing, understanding dead ends, and finally concluding with the best fitting solution.

Typographic experimentation by Sibylle Hagmann.

In a process oriented design education this iterative process has to be exercised over and over again, like exercising an instrument. In this model of design education the focus is on learning how to approach a systematic method over a narrowly defined audience. The ambiguity of viewership is hence merely defined as a point of departure and serves as a measurement of success or failure. The mystique in either situation allows for a process that differentiates from a layman’s approach.

Further typographic experimentation by Sibylle Hagmann.

In our last interview, Mr. Keedy posed this pair of questions: “Should we be surprised that (contemporary design work from grad schools) looks similar? When everyone has the same on-line education and uses the same software what do you think the outcome will be?” I am curious as to your thoughts regarding the flattening of aesthetics in North America.

Aside from the same software and online education, ‘Likes’ and ‘Hearts’ have become omnipresent built-in feedback-loops as a manifestation of confirmation of socially-shared results. There are plenty of style-look-books out there, and I presume that there’s a certain enticement to truncate the critical thinking and developing process for more immediate gratification with mimicry to harvest those thumbs up. In the process quality, depth and complexity risk to get lost.

The work of Sibylle’s student Cecilia Castellanos.

Also, while some grad students will end up in academia, others won’t. In post-recession, right-leaning times, grad schools are possibly drawn and pressured to orient themselves to corporate work that typically doesn’t tell a poetic visual story enhanced by inventive form.

Sibylle’s Axia family.

Where did you get the most experience teaching design?

As part of a team of four full-time faculty, I’ve been teaching a spectrum of graphic design related courses in the School of Art at the University of Houston over the past 14 years. That’s where the majority of teaching experience comes from. I learned a tremendous amount from my remarkable colleagues. It’s been quite a journey and there’s always more to come!

Sibylle’s Elido family.

As a critically-oriented designer, where do you see design criticism heading?

Mmh, somehow I feel like design criticism has taken a nap. And, it’s still napping, right? I mean it’s happening, but it’s not something that has been hotly debated lately here in the US. In the last couple of years, practicing designers may have been more interested in surviving an economic crisis than contemplating design criticism.

In my mind and from a US perspective, design criticism has several tasks at hand: critique its own discipline, provide theoretical discussions and, perhaps most importantly, improve the general public’s appreciation of design; its relationship is understated as is, and its role as a cultural contributor to society is vaguely acknowledged. We have to keep arguing for the relevance of the discipline in society and discuss these contributions for effectiveness, quality and relevance.

Sibylle’s Cholla family.

The root of contributing to criticism also reaches into design education: faculty is preoccupied with ever-changing technology and vocational studio-oriented training to provide industry-ready graduates. Educators are constantly sorting out what kind of designer (author, collaborator, entrepreneurial, sustainable, social, etc.) to propagate desperately seeking the public’s recognition and appreciation of design.

Speaking as a design educator, we have an obligation to kindle and promote diverse modes of research, and as faculty we are expected to do so, but find ourselves on slightly wobbly ground finding opportunities for funded (design) research projects, and making time to actively contribute to criticism oriented discussions.

So, I’m afraid I don’t have a clear-cut answer and I guess time will tell where design criticism is heading…

Sibylle’s Kopius family.

What are major or minor influences on your work? Just anything—be it writing, design, or other that has helped spur you forward as a maker and thinker.

Undeniably, the two contrasting mindsets and philosophies of the Basel School of Design, and CalArts have a lasting influence on my work. Beyond that, I admire creative work that has conviction; work that speaks of a thought process and that developed organically along a line undeterred by fashion. I’m not talking about aesthetics; it’s the notion of the work that intrigues me: the dexterity to aim for an evolved outcome, a certain work ethic and commitment to go on despite the struggle.

Sibylle’s Odile family.

In short I’m trying to orient myself in work that speaks of independence, and refinement, be it design, art, film, dance, writing, or music. Besides, the skill, talent and passion of a number of type designers, living and passed on, whom I very much admire keep spurring me on of course.

Sounds good—thank you very much, Sibylle! Be sure to check out Sibylle’s type foundry Kontour, as well as her collections of typographic experimentation online here.

And that wraps up another installment of “Huh?”, folks… Stay tuned for more interviews soon!latest jordans | Upcoming 2021 Nike Dunk Release Dates – Iebem-morelos