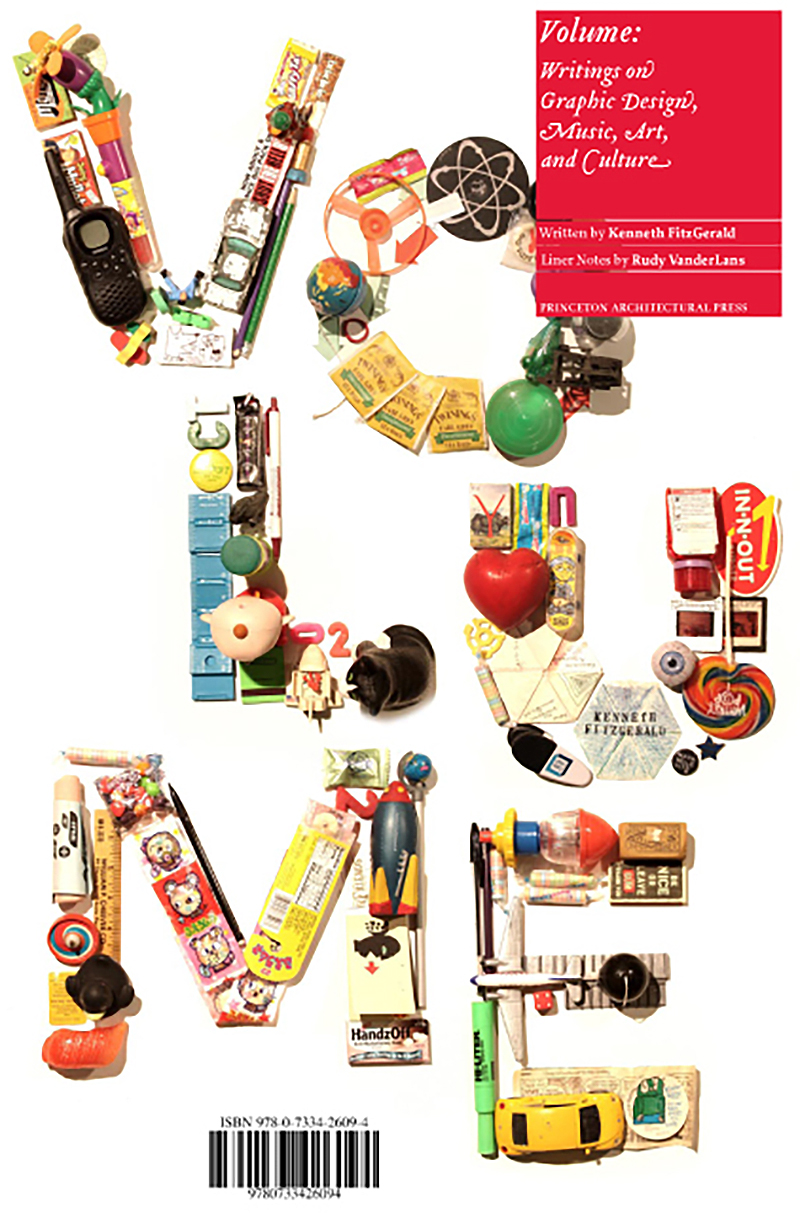

Kenneth FitzGerald is an educator, writer, designer, and artist—likely best known for the second. He is author of Volume: Writings on Graphic Design, Music, Art, and Culture (published in 2010 by Princeton Architectural Press) and was a regular contributor to Emigre magazine.

His writings have also appeared in (amongst others) Eye, Étapes, and Idea magazines; the books Graphic Design and Reading, The Education of a Graphic Designer volume 2, and the upcoming The Graphic Design Reader; plus the online journals Voice: AIGA Journal of Graphic Design, Design Observer, and Speak Up. He also wrote the forward for Stefan Sagmeister’s ggg Books monograph, was a guest in the third year of Design Matters with Debbie Millman, and has been a visiting critic for Cranbrook Academy of Arts 2D Design program, the School of Visual Arts Masters in Branding, and other places you may not suspect.

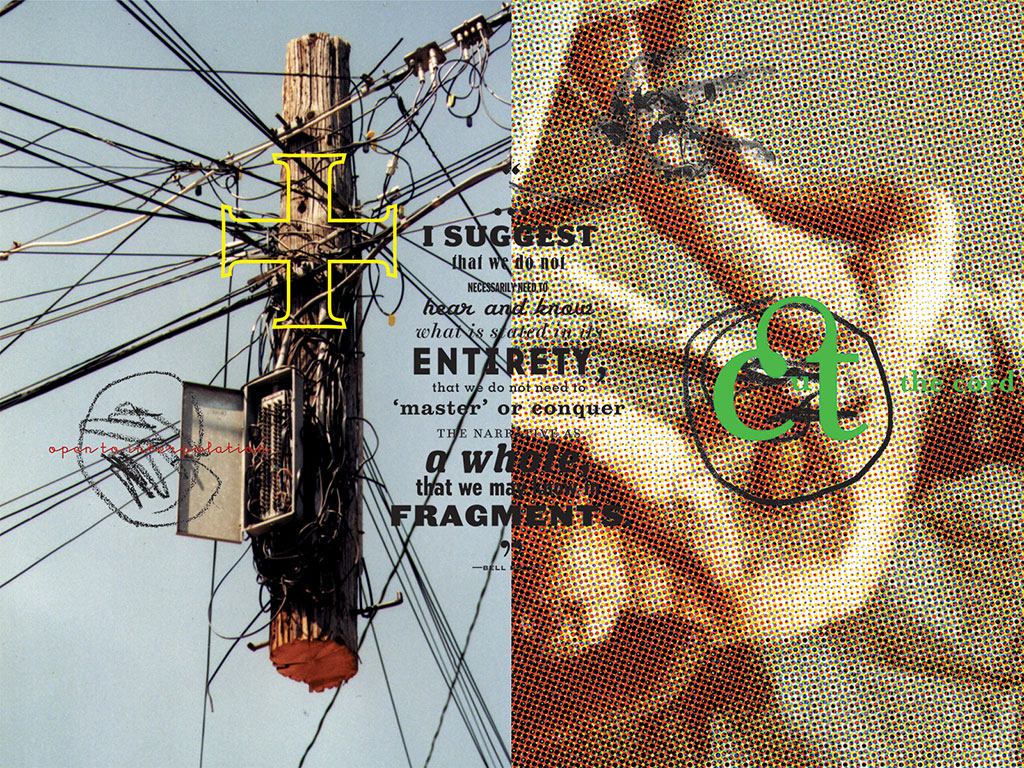

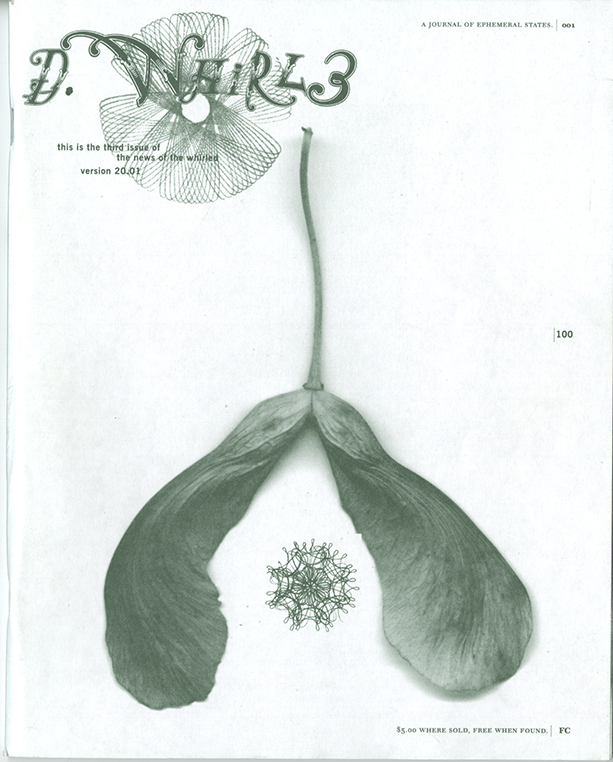

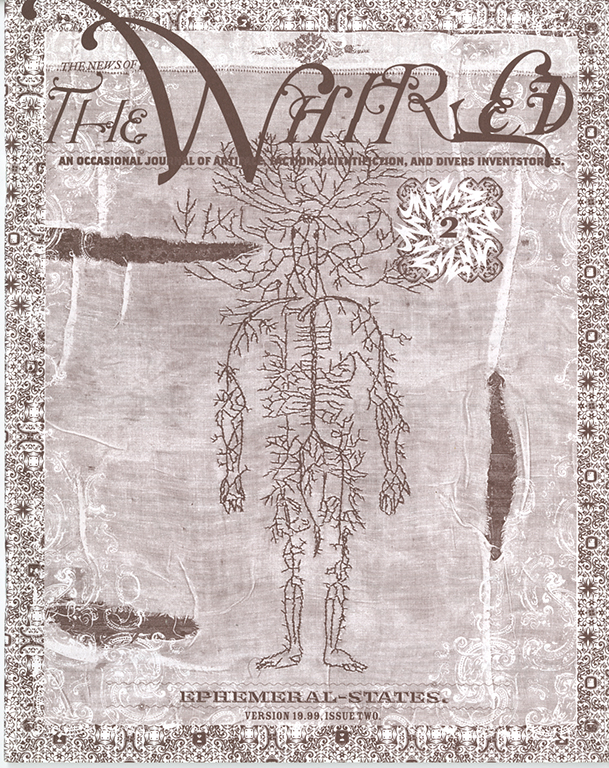

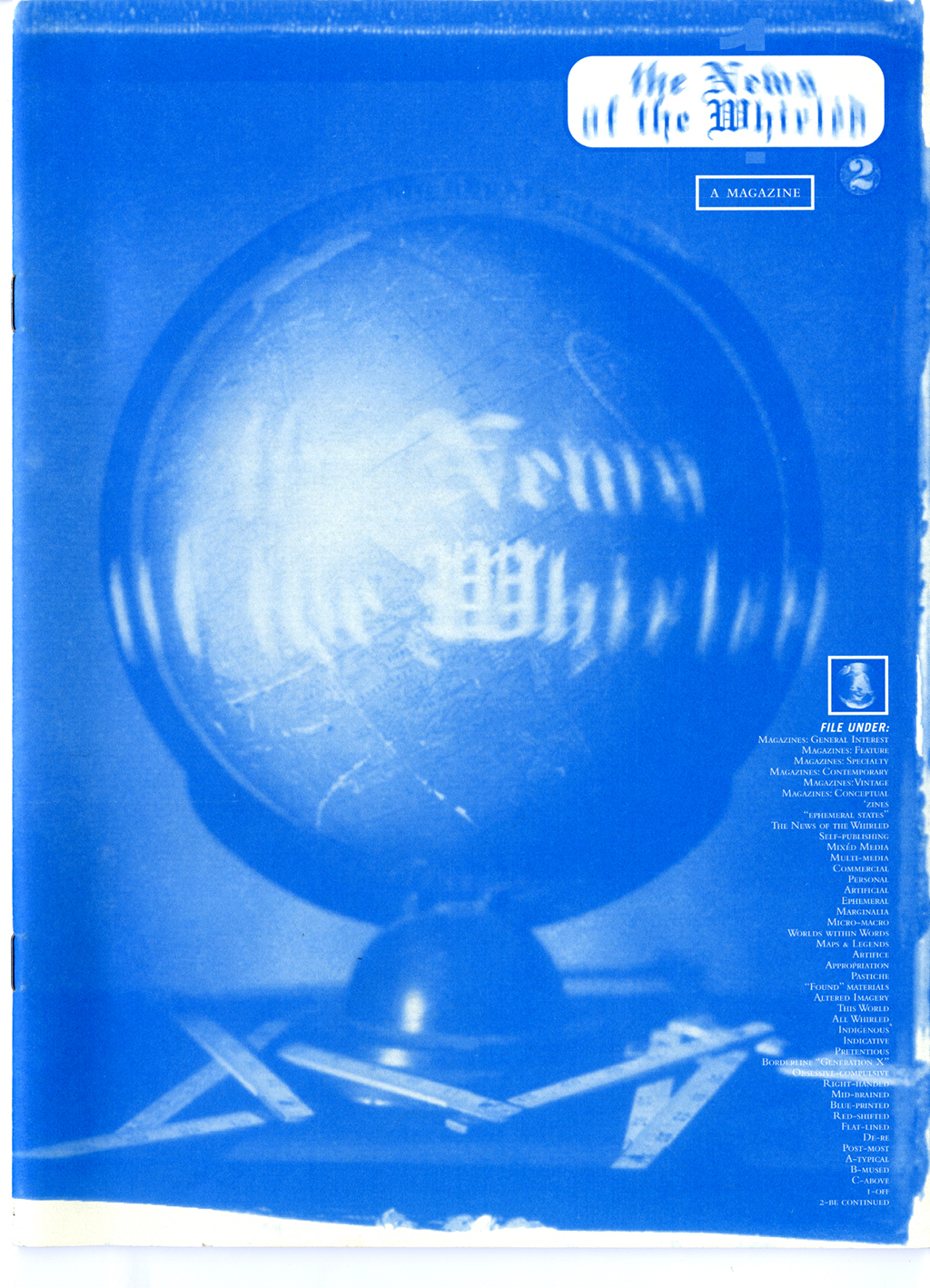

He produced The News of the Whirled, a novel as 4-issue limited-edition magazine that received awards for excellence from the American Center for Design and AIGA. His artwork is included in public and private collections in New England and New York, and the Franklin Furnace/Museum of Modern Art/Artists Books collection. Currently, he’s a Professor of Art at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia, on the steering committee of the AIGA Design Educators Community, and erratically maintains his blog www.ephemeralstates.com.

Ian Lynam takes some time to chat with Kenneth about writing, design, authorship and more.

In your recent essay “Fuck All”, you write about the importance of graphic authorship—how is it that you perceive graphic authorship to have changed or evolved over the past decade?

Actually, I didn’t, though I can understand the impression. The article isn’t meant as a celebration or defense of graphic authorship: it’s an answer to the question, “What is it about the concept of graphic authorship that so frightens Michael Rock?” Here’s this problematic concept/activity that is so alarming to Rock that he considers it necessary to intellectually hollow out design—to insist it’s nothing more than an intentionless formal exercise, that you’re deluded to think design can be or ever was anything more. It’s like curing an infection by removing everything but the patient’s epidermis then proclaiming them whole. Whatever you think of graphic authorship’s viability or efficacy—or if it even exists—it’s hard to claim it’s been anything but a fleeting, marginal force. So, why does Rock (and others) go after it so vehemently and protractedly? I’m just outlining the existential crisis it presents for traditionalist, fame-seeking designers.

By the way, I think this happens fairly often with my writing, where people think I’m advocating a particular position when I’m actually critiquing something on its own terms. For instance, when I criticize the design field for not supporting critical writing, it’s not about me and what I want. It’s the design field that claims it wants criticism: by doing things like venerating Massimo Vignelli’s “Call for Criticism.” I’m just pointing out that design isn’t following through or is contradicting itself.

Now, ask me what I think, and you might be surprised by the answer.

OK, then—so what do you think?

How much space do we have? Working backwards, I find it edifying and entertaining to read critical writing about graphic design, so I want more of it. And, of course, I enjoy writing it. But I don’t think I’m owed a readership or a forum just because I deign to do so.

I also have no problem with designers saying critical writing offers them nothing and they aren’t interested in reading or supporting it. Most designers are just fine with the existing elite-client-serving-based hierarchy that determines value. As long as they don’t lament about their practice being under-appreciated. If you want any kind of cultural currency that’s worthwhile and sticks, you’re got to go critical.

As far as graphic authorship, it’s a tool to wrest the conception of design away from the client-service-centric model imposed by the profession. But it’s nothing I actively use to shape my activity, though much of what I do would appear to be “graphic authorship.” As to what’s happened over the past decade, it’s either underground or hardly daring to speak its name. By his own admission, Michael Rock’s oft-cited Eye article on the phenomenon was intended to not so much examine but extinguish graphic authorship. With that article promoted as the definitive take, it didn’t have much of a chance.

You write design criticism from a contemporary standpoint—though often referencing history—what is “contemporary” and how do you write about something as it is being experienced?

The referencing history aspect is the important part, of having an awareness that some things have gone before. It’s difficult to get beyond the aspects of the historical moment when you’re in that historical moment but not impossible. Looking at old photos of myself — or reading my old essays — will remind me. Just to have that awareness goes a long way. It’s not about avoiding getting caught up with transient surface treatments — I love wallowing in transient surface treatments — it’s putting them in context.

In the same essay, you write, “Design isn’t a glossy and empty abstraction of itself. It’s by and for people. Our content is, perpetually, ourselves.” How is it that you propose designers might inject themselves into the work further?

To design for the people in front of you and not abstracted entities like “graphic design,” “users,” “consumers,” and so forth. It’s relocating your ego so it’s about having a mutually rewarding experience with a commissioner (everyone else would put “client” here) instead of a determination to craft a signature artifact for a stereotyped audience.

One of the great tropes of Modernism was the injection of the rhetoric of ‘problem-solving’ into graphic design—of self-importance and officiousness. It is still something that is highly prevalent in the discourse. Is there some trope or topic that you feel exemplifies, or at least feels like a contemporary parallel in design discourse today?

Problem-solving is still a deeply-embedded tick that hasn’t lost any of its potency, so I’m keen to keep tweezers at the ready. But there are always new buzzy candidates that emerge from design. One I find particularly irksome is the whole “compromise” delusion — that it’s a bad thing and designers must fight any deviation from their designated formal course.

The practice of writing is something that most people don’t have a designated schedule for. When do you write? And perhaps more importantly, why do you write?

When is whenever I find the time and motivation to start. If I can start, it carries itself and I’m eager to sneak in time everywhen. I used to stay up late but I get tired easier and lose my space in bed to the cats. The why is easy: I write for me, even in those rare instances when someone will ask me to write something. I write because I have ideas or questions about things and wonder, “Am I the only one thinking this?” Most of the time, the answer is yes, so if I want to work out what I think and what it means, I have to write.

What are things that you think every designer should read in terms of edification?

Things that are antithetical to their deeply held and treasured beliefs about design.

What are your guilty pleasures in terms of reading?

I think I purged the guilt reflex some time ago when it comes to pleasures, though I can be teased. But if you mean things I’ll pick up anytime and indulge in, science fiction. Or Lester Bangs’ album reviews.

And thus ends the latest installment of “Huh?”. We are immensely looking forward to having Kenneth join us as critic, workshop leader and lecturer at our next residency in April. Thank you, Kenneth!

More “Huh?” coming soon!